In Pardis, a satellite city northeast of Tehran, nearly half the buildings remain unfinished. There is no subway between Tehran and these satellite cities. For residents who work in the capital, the commute can take hours each way.

‘Four decades after the Revolution, the population has grown by almost fifty million; the number of households has quadrupled. Teeming, polluted Tehran can no longer hold all those who need or want to live there.’

It’s time we recognise how harmful rapid population explosion can be for a country and how devastating high-rise living can be for residents.

GHOST TOWERS*

The view from Iran’s housing crisis.

‘After the Iranian Revolution, in 1979, the theocracy called on women to breed a new Islamic generation. It lowered the marriage age to nine for girls and fourteen for boys; it legalized polygamy and raised the price of birth control. By 1986, the average family had six children. A leading cleric said that the government’s goal was to increase the number of people who believed in the Revolution in order to preserve it. The population surge coincided with mass migration to Iran’s cities, spurred first by Iraq’s invasion, in the eighties, and then by the lure of jobs and education, in the nineties. The government introduced family planning, which brought the average family size down to two children, but Iran still struggled to feed, clothe, educate, employ, and house its people. Four decades after the Revolution, the population has grown by almost fifty million; the number of households has quadrupled. Teeming, polluted Tehran can no longer hold all those who need or want to live there.

The government responded to the housing shortage by building satellite towns of sterile high-rises on barren land far from the capital. They were supposed to be affordable, ready-made utopias with modern utilities for low-income and middle-class workers who couldn’t afford Tehran. But the early apartments had faulty sewage systems and heating, inadequate access to water, and only intermittent electricity. Many were destroyed in the earthquake of 2017.

Economic pressures have forced some residents to work as street venders to supplement their income.

Hashem Shakeri first glimpsed some of these ghostly concrete towers on a weekend drive in 2007. He was baffled by the idea that Iranians would be expected to live in the austere structures. “They were like a remote island,” he told me. “When I thought about the people who were supposed to come and live there, I couldn’t even breathe.” In 2016, he began to photograph the satellite towns and their residents. He started in Pardis; the name is Persian for “paradise.”

“Most of the people who came there had lost something in their lives,” Shakeri said. “They had been employees who used to receive monthly payments. After the economic crisis, they couldn’t make ends meet.” There were few parks, playgrounds, or social outlets, and limited signs of life outside the high-rises. To capture the sterility and the eerie quiet in the satellite towns—including Pardis and Parand—he took the photographs using medium-format film, in direct sunlight, and overexposed them.

He said, “I wanted my audience to see the bitterness that applies to all of those towns,” many of whose residents travel hours each day to jobs in Tehran. “There is a recurrent, vicious cycle where people are sleep-deprived—they have to wake up early and work late to commute to Tehran, which takes a lot of time. They only sleep in the towns. Like Sisyphus, they have to repeat the cycle over and over.”

“I asked people if they were satisfied living in these cities,” Shakeri said. “Most of them answered, ‘Thank God—we have no other way.’ ”

The country’s housing crisis deepened after President Trump withdrew from the Iran nuclear deal, in May, 2018, and reimposed economic sanctions six months later. The rial is now down by sixty per cent, and real-estate prices in Tehran have more than doubled. Yet tens of thousands of apartments in the new towns are empty, because, though they are cheaper, many Iranians still can’t afford them. Shakeri, like other Tehran residents, feels the squeeze. He told me that, as he took the photographs, “I was worried that I may be one of the people who have to leave Tehran and move into one of these apartments.”- Robin Wright. Photographs by Hashem Shakeri

*Read the original article here

The Tragedy of High-Rises: The Loss of Knowing Who, Why and What We Are and What it Means to be Human

The Loss of Relationship and Connection with Sacred Earth and Mother Nature with the accompanying rise in Mental Illness, Fear, Loneliness, Anxiety, Stress and Depression

What was highlighted above, is not just an issue in Iran. The tragedy is global.

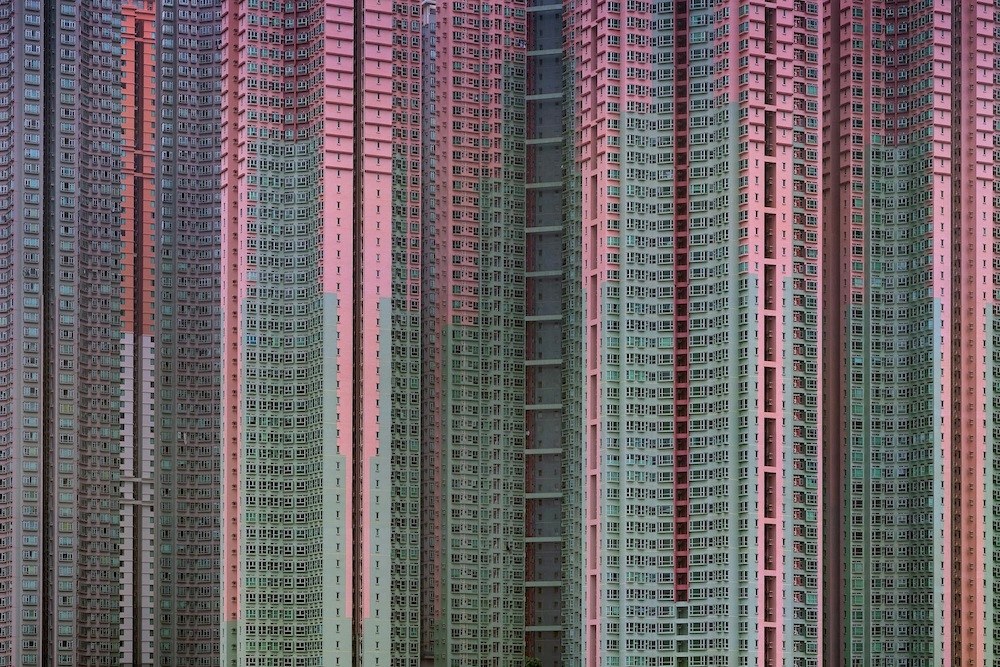

Photo:BBC-FUTURE

‘Today, millions of people live in high-rise apartment blocks around the world. In Moscow alone, there are 11,783 high-rise towers, in Hong Kong there are 7,833, and in Seoul there are over 7,000, many of which are residential. Understanding the link between high-rise living and mental health is crucial to protect the well-being of tower block residents across the globe.

High-rise living evokes unsettling fears – residents could be trapped in a fire, or fall or jump from the tower. The sheer number of people sharing a single building can also increase the threat from communicable diseases such as influenza, which spread easily when hundreds of people share a building’s hallways, door handles and lift buttons.

The Tragedy of High-Rises: The Case of Britain

Sharing semi-public spaces with strangers can make residents more suspicious and fearful of crime. Many feel an absence of community, despite living alongside tens or hundreds of other people. And in earthquake-prone countries, residents of high-rise towers face the possibility that their entire building could collapse.

Perhaps most poignant of all is the fear of isolation. During ongoing research into social isolation among older people in the English city of Leeds, residents of high-rise buildings reported feeling lonely and isolated – some were afraid to even open their front doors.

Many of these older residents rely on networks of neighbours, friends and family to help them get around and perform basic chores. One wheelchair user explained how she relied on her neighbour to help her get to the lift and out of the block. If her neighbour is not there, she is stuck.

Living with fear every day means that residents of high-rise housing – and especially social housing – are vulnerable to mental health issues. Psychologists have been investigating this link since the 1970s – a 1979 study based in Glasgow found evidence that high-rise residents were presenting psychological symptoms more often than other housing residents.

Another paper from 1991 compared elderly African-Americans living in high-rise and low-rise buildings in Nashville. The high risers had a higher incidence of depression, phobias, schizophrenia.

The true causes?

But researchers aren’t always comparing like with like. In Nashville, although the residents shared the same ethnic background, high risers were poorer, less educated and had fewer social contacts: all factors which may contribute towards mental ill health.

So it’s difficult to say whether it’s the building itself, or other hardships such as poverty, which cause high-rise residents such difficulties. Yet there is some evidence to suggest that high-rise buildings themselves are actually responsible for some of the harm done to residents.

For example, in Singapore, between 1960 and 1976, the percentage of people living in high-rise buildings climbed from 9 per cent to 51 per cent. During the same period, the per capita rate of suicides by leaping from tall buildings increased fourfold, while suicide by other means declined.

This could be for one of two reasons. Either more people became suicidal and would have found a way to commit suicide by any means – or greater access to tall buildings gave more people a means of killing themselves, which they wouldn’t otherwise have done.

The overall suicide rate in Singapore increased by 30 per cent over the aforementioned period but the rate by leaping increased many times faster, which suggests that having more tall buildings leads to more suicides. While suicide rates have been stable for five decades now, jumping from buildings remains a common method for suicide there, as well as in other cities where high rise buildings are ubiquitous – such as Hong Kong, New York City, Taipei City.’...This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

TOWERING ASPIRATIONS OR THE HEIGHT OF MADNESS?

Photo:wired.com

‘As our world becomes increasingly urbanized and mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety become seemingly more prevalent, it is time we pause and consider ways to alleviate this stress. Growing numbers of psychologists claim that several of our modern stressors are due to a departure from the natural world. Since industrialization, we have become disconnected from our relationship with nature. However, there is a solution…’

Especially at risk are the Millennial burnouts, the youth, our future leaders: It’s all about being hyper-healthy, hyper-clued-up, hyper-fashionable, hyper-achiever, be best, be perfect,... - and this is too exhausting, too draining.

Together, We Hold the Future in Our Hands

We must not fail our children and grandchildren. We must do the right thing. We must save the web of life

At the GCGI we believe every person, young and old, should have regular opportunities and ease of access to connect with nature, so they can learn to value it, appreciate it, enjoy it, prioritise it and take action to save it.

“Be like the sun for grace and mercy.

Be like the night to cover others’ faults.

Be like running water for generosity.

Be like death for rage and anger.

Be like the Earth for modesty.

Appear as you are.

Be as you appear.”-Rumi

'Humans have long been deeply moved by a still expanse of water, a deep forest, a mountain peak. After all, nature is where we find our soul and come into contact with our spirituality. Yet, most people today live in cities and spend far less time outside in green, natural spaces than the populations of only a few generations ago.’

Nature heals, Nature soothes, Nature restores, Nature connects: Yes, Nature is what makes us Human!

‘Being in nature, or even viewing scenes of nature, reduces anger, fear, and stress and increases pleasant feelings. Exposure to nature not only makes you feel better emotionally, it contributes to your physical wellbeing, reducing blood pressure, heart rate, muscle tension, and the production of stress hormones. It may even reduce mortality. Research done in hospitals, offices, and schools has found that even a simple plant in a room can have a significant impact on stress and anxiety.’

‘Psychoterratica is the trauma caused by distance from nature’

The high costs of nature deprivation

Are you physically and emotionally drained? I know of a good and cost-free solution!