'People have strong, divergent opinions about the continuity of their own selves.'

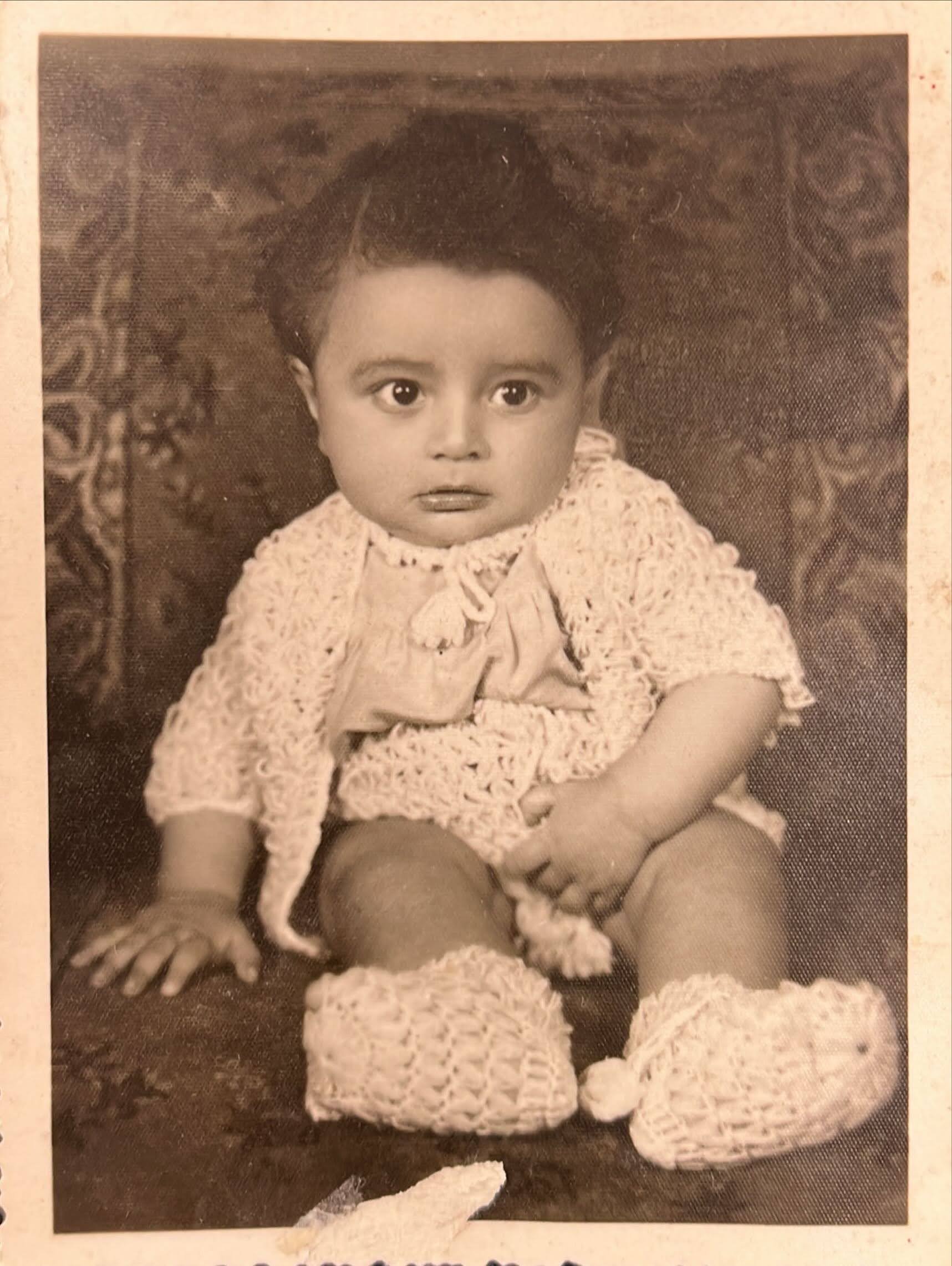

I don’t know about you, but as I have been getting older, a question or two has been occupying my thoughts and moments of reflection, especially when I am on my own, that is me, myself and I. Who Was I and Who Am I Now? Am I the same person now as I was way back? What has changed and what is continuing?

I suppose like many others, I have both a deep sense of continuity and a deep sense of differences between then and now. I hope that my continuities will be with me forever, love and being loved, hope and hopefulness, gratitude and gratefulness, optimism and positivity, courage and the willingness to engage no matter the consequence.

If these and other similar questions are in your thoughts and reflections too, Then, perhaps the posting below will be helpful to you as it has been to me.

Illustration by Juan Bernabeu

‘Joshua Rothman poses a thought experiment in a fascinating essay in this week’s issue of the New Yorker: “Try to remember life as you lived it years ago, on a typical day in the fall. . . . Does the self you remember feel like you, or like a stranger? Do you seem to be remembering yesterday, or reading a novel about a fictional character?” How you answer that question likely reflects whether you view your life as an uninterrupted narrative of a single self or an episodic story with a main character who’s changing—maybe slightly, maybe entirely—over time. Are you the same person today that you were when you were six, or sixteen? Do you want to be? And, perhaps more vitally, how would you even know for sure? Rothman surveys the ways that artists and researchers have approached these questions, and considers how internal and external factors shape our understanding of self, what it takes for people to really change, and if we can rightly claim to be the authors of our own life stories. It’s a trip—even if we’re travelling a shorter distance than we imagine.’-—Ian Crouch, The New Yorker newsletter editor

…’Try to remember life as you lived it years ago, on a typical day in the fall. Back then, you cared deeply about certain things (a girlfriend? Depeche Mode?) but were oblivious of others (your political commitments? your children?). Certain key events—college? war? marriage? Alcoholics Anonymous?—hadn’t yet occurred. Does the self you remember feel like you, or like a stranger? Do you seem to be remembering yesterday, or reading a novel about a fictional character?

'If you have the former feelings, you’re probably a continuer; if the latter, you’re probably a divider. You might prefer being one to the other, but find it hard to shift your perspective. In the poem “The Rainbow,” William Wordsworth wrote that “the Child is Father of the Man,” and this motto is often quoted as truth. But he couched the idea as an aspiration—“And I could wish my days to be / Bound each to each by natural piety”—as if to say that, though it would be nice if our childhoods and adulthoods were connected like the ends of a rainbow, the connection could be an illusion that depends on where we stand. One reason to go to a high-school reunion is to feel like one’s past self—old friendships resume, old in-jokes resurface, old crushes reignite. But the time travel ceases when you step out of the gym. It turns out that you’ve changed, after all…’

‘The passage of time almost demands that we tell some sort of story.’

Rainbow Clock is a piece of digital artwork by Mateo Antonio.

…‘The passage of time almost demands that we tell some sort of story: there are certain ways in which we can’t help changing through life, and we must respond to them. Young bodies differ from old ones; possibilities multiply in our early decades, and later fade. When you were seventeen, you practiced the piano for an hour each day, and fell in love for the first time; now you pay down your credit cards and watch Amazon Prime. To say that you are the same person today that you were decades ago is absurd. A story that neatly divides your past into chapters may also be artificial. And yet there’s value in imposing order on chaos. It’s not just a matter of self-soothing: the future looms, and we must decide how to act based on the past. You can’t continue a story without first writing one.

‘Sticking with any single account of your mutability may be limiting. The stories we’ve told may become too narrow for our needs. In the book “Life Is Hard,” the philosopher Kieran Setiya argues that certain bracing challenges—loneliness, failure, ill health, grief, and so on—are essentially unavoidable; we tend to be educated, meanwhile, in a broadly redemptive tradition that “urges us to focus on the best in life.” One of the benefits of asserting that we’ve always been who we are is that it helps us gloss over the disruptive developments that have upended our lives. But it’s good, the book shows, to acknowledge hard experiences and ask how they’ve helped us grow tougher, kinder, and wiser. More generally, if you’ve long answered the question of continuity one way, you might try answering it another. For a change, see yourself as either more continuous or less continuous than you’d assumed. Find out what this new perspective reveals.

‘There’s a recursive quality to acts of self-narration. I tell myself a story about myself in order to synchronize myself with the tale I’m telling; then, inevitably, I revise the story as I change. The long work of revising might itself be a source of continuity in our lives. One of the participants in the “Up” series tells Apted, “It’s taken me virtually sixty years to understand who I am.” Martin Heidegger, the often impenetrable German philosopher, argued that what distinguishes human beings is our ability to “take a stand” on what and who we are; in fact, we have no choice but to ask unceasing questions about what it means to exist, and about what it all adds up to. The asking, and trying out of answers, is as fundamental to our personhood as growing is to a tree.

‘Recently, my son has started to understand that he’s changing. He’s noticed that he no longer fits into a favorite shirt, and he shows me how he sleeps somewhat diagonally in his toddler bed. He’s been caught walking around the house with real scissors. “I’m a big kid now, and I can use these,” he says. Passing a favorite spot on the beach, he tells me, “Remember when we used to play with trucks here? I loved those times.” By this point, he’s actually had a few different names: we called him “little guy” after he was born, and I now call him “Mr. Man.” His understanding of his own growth is a step in his growing, and he is, increasingly, a doubled being—a tree and a vine. As the tree grows, the vine twines, finding new holds on the shape that supports it. It’s a process that will continue throughout his life. We change, and change our view of that change, for as long as we live.’- Continue to read the article (Published in the print edition of the New Yorker on October 10, 2022, issue, with the headline “Becoming You.”

Who Was I and Who Am I Now?

Me Circa 1953

Me at 70 years old, March 2022

N.B. Joshua Rothman, the author of ‘Becoming You’ has tasked us all with a challenge, which is that we should become ‘storytellers’! He writes: ‘The passage of time almost demands that we tell some sort of story.’ This very much resonates with me. A couple of decades ago, facing multiples of mis-life challenges, I found solace in telling stories and I became a storyteller. I have found this to be healing, comforting and reassuring. Above all, I have also discovered who I am and who I have become. I highly recommend this to everyone. Write your stories, recall your journeys, as I have.

Coventry and I: The story of a boy from Iran who became a man in Coventry

Celebrating the Gift and Miracle of Ageing: Giving Thanks as I Approach 70

Thank you England for 50 blissful years

Journey to Healing: Let Me Know What is Essential

With all my love and gratitude,

Kamran