William Wordsworth ( 7 April 1770- 23 April 1850)

The first eco-warrior

The great champion of plain speech (“the language really used by men”), the radical poet of empathy with those on the margins and the rural poor, the most persuasive of all environmentalists.

Happy Birthday, William Wordsworth! Our greatest nature poet. The World needs your wisdom more than ever now.

“Nature is a teacher whose wisdom we can learn, and without which any human life is vain and incomplete.”

Nota bene

To honour Wordsworth 250th birthday I offer you the following, which I sincerely believe speaks to us all at this time of global crisis. May this soothe you and be a path of healing and hope to you, as it has been for me.

William Wordsworth and the triumph of spirit

When a tsunami of crisis hit him on the shores of fear, hopelessness, helplessness, self-doubt and destruction, he let nature to embrace him to give him hope for better days to come.

In times of uncertainty, crisis and confusion let nature be your refuge, your saviour, as William Wordsworth did so convincingly.

A shared crisis connects us all: Let the spirit of nature be what will bring us together, moving us from darkness to light, winter to spring. Nature is also a symbol of renewal and regeneration that we need at the moment. Therefore, as Wordsworth has asked us: ‘Let Nature be Your Teacher.’

“Nature is a teacher whose wisdom we can learn, and without which any human life is vain and incomplete.”

To this end, it is my pleasure to offer you the following to acknowledge and celebrate the 250th Birthday of William Wordswoth, as a way of connecting each other with nature and hope for the future.

Yes, it is true: Nature heals, Nature soothes, Nature restores, Nature connects: Yes, Nature is what makes us Human.

The Tables Turned

BY WILLIAM WORDSWORTH

Up! up! my Friend, and quit your books;

Or surely you'll grow double:

Up! up! my Friend, and clear your looks;

Why all this toil and trouble?

The sun above the mountain's head,

A freshening lustre mellow

Through all the long green fields has spread,

His first sweet evening yellow.

Books! 'tis a dull and endless strife:

Come, hear the woodland linnet,

How sweet his music! on my life,

There's more of wisdom in it.

And hark! how blithe the throstle sings!

He, too, is no mean preacher:

Come forth into the light of things,

Let Nature be your teacher.

She has a world of ready wealth,

Our minds and hearts to bless—

Spontaneous wisdom breathed by health,

Truth breathed by cheerfulness.

One impulse from a vernal wood

May teach you more of man,

Of moral evil and of good,

Than all the sages can.

Sweet is the lore which Nature brings;

Our meddling intellect

Mis-shapes the beauteous forms of things:—

We murder to dissect.

Enough of Science and of Art;

Close up those barren leaves;

Come forth, and bring with you a heart

That watches and receives.

William Wordsworth, The Environmentalist and a Poet of Nature

Various portraits of William Wordsworth via The Society of Classical Poets

‘As a poet of Nature, Wordsworth stands supreme. He is a worshipper of Nature, Nature’s devotee or high-priest. His love of Nature was probably truer, and more tender, than that of any other English poet, before or since. Nature comes to occupy in his poem a separate or independent status and is not treated in a casual or passing manner as by poets before him. Wordsworth had a full-fledged philosophy, a new and original view of Nature. Three points in his creed of Nature may be noted:

(a) He conceived of Nature as a living Personality. He believed that there is a divine spirit pervading all the objects of Nature. This belief in a divine spirit pervading all the objects of Nature may be termed as mystical Pantheism and is fully expressed in Tintern Abbey and in several passages in Book II of The Prelude.

(b) Wordsworth believed that the company of Nature gives joy to the human heart and he looked upon Nature as exercising a healing influence on sorrow-stricken hearts.

(c) Above all, Wordsworth emphasized the moral influence of Nature. He spiritualised Nature and regarded her as a great moral teacher, as the best mother, guardian and nurse of man, and as an elevating influence. He believed that between man and Nature there is mutual consciousness, spiritual communion or ‘mystic intercourse’. He initiates his readers into the secret of the soul’s communion with Nature. According to him, human beings who grow up in the lap of Nature are perfect in every respect.

Wordsworth believed that we can learn more of man and of moral evil and good from Nature than from all the philosophies. In his eyes, “Nature is a teacher whose wisdom we can learn, and without which any human life is vain and incomplete.” He believed in the education of man by Nature. In this he was somewhat influenced by Rousseau. This interrelation of Nature and man is very important in considering Wordsworth’s view of both.

Cazamian says that “To Wordsworth, Nature appears as a formative influence superior to any other, the educator of senses and mind alike, the sower in our hearts of the deep-laden seeds of our feelings and beliefs. It speaks to the child in the fleeting emotions of early years, and stirs the young poet to an ecstasy, the glow of which illuminates all his work and dies of his life.”.

Development of His Love for Nature

Wordsworth’s childhood had been spent in Nature’s lap. A nurse both stern and kind, she had planted seeds of sympathy and under-standing in that growing mind. Natural scenes like the grassy Derwent river bank or the monster shape of the night-shrouded mountain played a “needful part” in the development of his mind. In The Prelude, he records dozens of these natural scenes, not for themselves but for what his mind could learn through.

Nature was “both law and impulse”; and in earth and heaven, in glade and bower, Wordsworth was conscious of a spirit which kindled and restrained. In a variety of exciting ways, which he did not understand, Nature intruded upon his escapades and pastimes, even when he was indoors, speaking “memorable things”. He had not sought her; neither was he intellectually aware of her presence. She riveted his attention by stirring up sensations of fear or joy which were “organic”, affecting him bodily as well as emotionally. With time the sensations were fixed indelibly in his memory. All the instances in Book I of The Prelude show a kind of primitive animism at work”; the emotions and psychological disturbances affect external scenes in such a way that Nature seems to nurture “by beauty and by fear”.

In Tintern Abbey, Wordsworth traces the development of his love for Nature. In his boyhood Nature was simply a playground for him. At the second stage he began to love and seek Nature but he was attracted purely by its sensuous or aesthetic appeal. Finally his love for Nature acquired a spiritual and intellectual character, and he realized Nature’s role as a teacher and educator.

In the Immortality Ode he tells us that as a boy his love for Nature was a thoughtless passion but that when he grew up, the objects of Nature took a sober colouring from his eyes and gave rise to profound thoughts in his mind because he had witnessed the sufferings of humanity:

To me the meanest flower that blows can give

Thoughts that do often lie too deep for tears.

Spiritual Meaning in Natural Objects

Compton Rickett rightly observes that Wordsworth is far less concerned with the sensuous manifestations than with the spiritual significance that he finds underlying these manifestations. To him the primrose and the daffodil are symbols to him of Nature’s message to man. A sunrise for him is not a pageant of colour; it is a moment of spiritual consecration:

My heart was full; I made no vows, but vows

Were then made for me; bound unknown to me

Was given, that I should be, else sinning greatly,

A dedicated Spirit.

To combine his spiritual ecstasy with a poetic presentment of Nature is the constant aim of Wordsworth. It is the source of some of his greatest pieces, grand rhapsodies such as Tintern Abbey.

Nature Descriptions

Wordsworth is sensitive to every subtle change in the world about him. He can give delicate and subtle expression to the sheer sensuous delight of the world of Nature. He can feel the elemental joy of Spring:

It was an April morning, fresh and clear

The rivulet, delighting in its strength,

Ran with a young man’s speed, and yet the voice

Of waters which the river had supplied

Was softened down into a vernal tone.

He can take an equally keen pleasure in the tranquil lake:

The calm

And dead still water lay upon my mind

Even with a weight of pleasure

A brief study of his pictures of Nature reveals his peculiar power in actualising sound and its converse, silence.

Being the poet of the ear and of the eye, he is exquisitely felicitous. No other poet could have written:

A voice so thrilling ne’er was heard

In springtime from the cuckoo-bird,

Breaking the silence of the seas

Among the farthest Hebrides.

Unlike most descriptive poets who are satisfied if they achieve a static pictorial effect, Wordsworth can direct his eye and ear and touch to convey a sense of the energy and movement behind the workings of the natural world. “Goings on” was a favourite word he applied to Nature. But he is not interested in mere Nature description.

Wordsworth records his own feelings with reference to the objects which stimulate him and calls forth the description. His unique apprehension of Nature was determined by his peculiar sense-endowment. His eye was at once far-reaching and penetrating. He looked through the visible scene to what he calls its “ideal truth”. He pored over objects till he fastened their images on his brain and brooded on these in memory till they acquired the liveliness of dreams. He had a keen ear too for all natural sounds, the calls of beasts and birds, and the sounds of winds and waters; and he composed thousands of lines wandering by the side of a stream. But he was not richly endowed in the less intellectual senses of touch, taste and temperature.

Conclusion:

Wordsworth’s attitude to Nature can be clearly differentiated from that of the other great poets of Nature. He did not prefer the wild and stormy aspects of Nature like Byron, or the shifting and changeful aspects of Nature and the scenery of the sea and sky like Shelley, or the purely sensuous in Nature like Keats. It was his special characteristic to concern himself, not with the strange and remote aspects of the earth, and sky, but Nature in her ordinary, familiar, everyday moods. He did not recognize the ugly side of Nature ‘red in tooth and claw’ as Tennyson did. Wordsworth stressed upon the moral influence of Nature and the need of man’s spiritual discourse with her.’- See the original source of this article

Wordsworth was one of the most influential of England's Romantic poets.

‘William Wordsworth was born on 7 April 1770 at Cockermouth in Cumbria. His father was a lawyer. Both Wordsworth's parents died before he was 15, and he and his four siblings were left in the care of different relatives. As a young man, Wordsworth developed a love of nature, a theme reflected in many of his poems.

While studying at Cambridge University, Wordsworth spent a summer holiday on a walking tour in Switzerland and France. He became an enthusiast for the ideals of the French Revolution. He began to write poetry while he was at school, but none was published until 1793.

In 1795, Wordsworth received a legacy from a close relative and he and his sister Dorothy went to live in Dorset. Two years later they moved again, this time to Somerset, to live near the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who was an admirer of Wordsworth's work. They collaborated on 'Lyrical Ballads', published in 1798. This collection of poems, mostly by Wordsworth but with Coleridge contributing 'The Rime of the Ancient Mariner', is generally taken to mark the beginning of the Romantic movement in English poetry. The poems were greeted with hostility by most critics.

In 1799, after a visit to Germany with Coleridge, Wordsworth and Dorothy settled at Dove Cottage in Grasmere in the Lake District. Coleridge lived nearby with his family. Wordsworth's most famous poem, 'I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud' was written at Dove Cottage in 1804.

In 1802, Wordsworth married a childhood friend, Mary Hutchinson. The next few years were personally difficult for Wordsworth. Two of his children died, his brother was drowned at sea and Dorothy suffered a mental breakdown. His political views underwent a transformation around the turn of the century, and he became increasingly conservative, disillusioned by events in France culminating in Napoleon Bonaparte taking power.

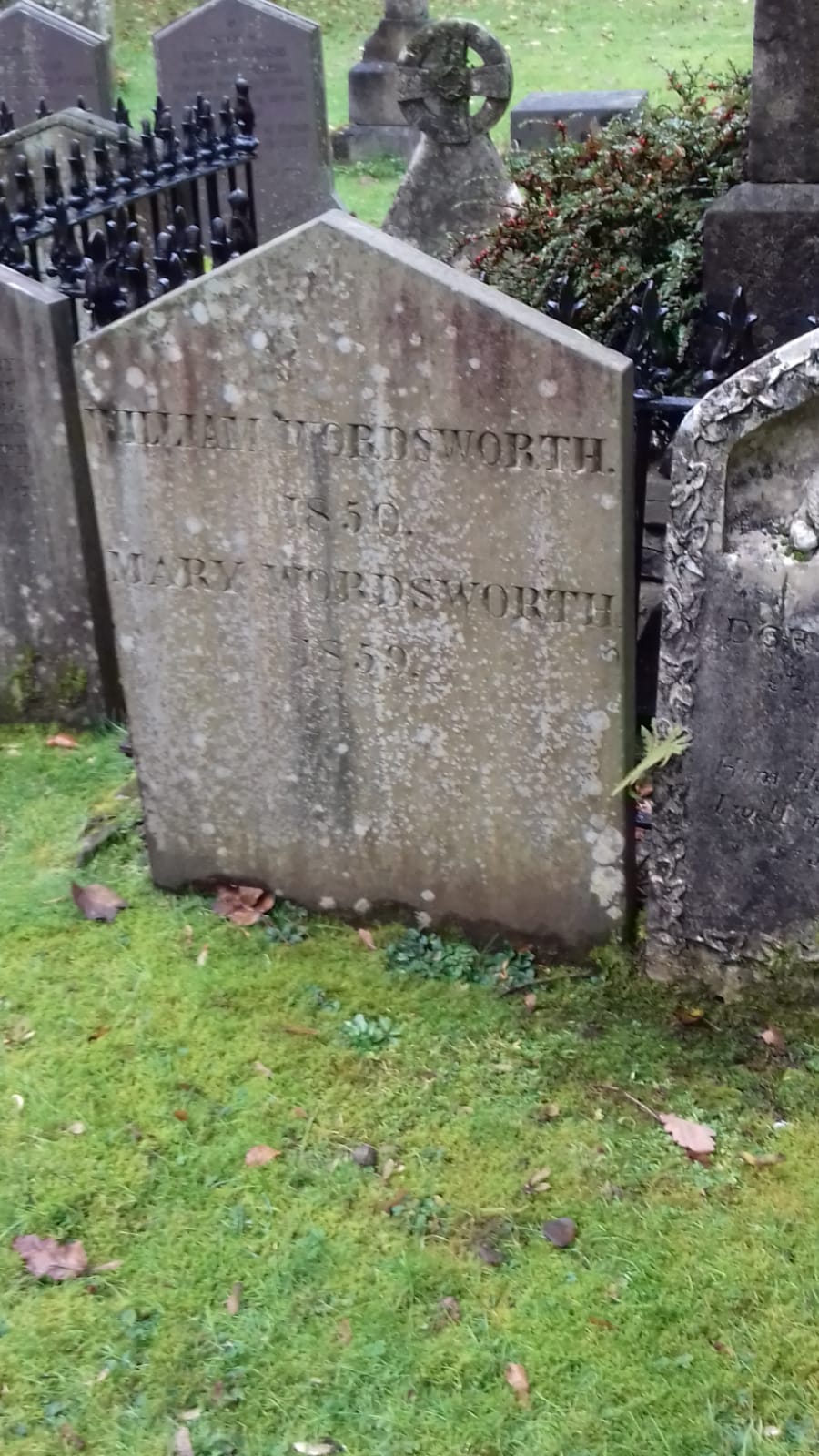

In 1813, Wordsworth moved from Grasmere to nearby Ambelside. He continued to write poetry, but it was never as great as his early works. After 1835, he wrote little more. In 1842, he was given a government pension and the following year became poet laureate. Wordsworth died on 23 April 1850 and was buried in Grasmere churchyard. His great autobiographical poem, 'The Prelude', which he had worked on since 1798, was published after his death.’- BBC History

Wordsworth's Legacy and Gift to the World:

In this troubled world let the beauty of nature and simple life be our greatest teachers

“William Wordsworth is Britain’s best-loved poet, whose thoughts, sentiments and writings about people, nature and society, are so topical and current they could have been written yesterday. Wordsworth is known to be a worshiper of Nature. His love of Nature is tender and truer than any other English poets. There is a separate status of Nature in his poems. He believed that there is a divine spirit in nature. He believed that the company of nature gives joy to the human heart and he looked upon nature as a healing force. Above all, he regarded her as a great moral preacher. He believed that there is a link between man and nature.In his eyes, "Nature is a teacher whose wisdom we can learn if we will, and without which any human life is vain and incomplete. "He believed in the education of man by nature. "Sweet is the lore which Nature brings”.

Beauty of Nature as appreciated by Wordsworth

‘Poetry, which came much before prose in human history, has been a vehicle for the spiritual and social progress in man. The natural world with its great beauty and mystery has long been a source of inspiration to poets. The Romantic poets like Wordsworth and Keats, who were active in the nineteenth century, experienced the most inspiration through nature, which they captured in their poetry. William Wordsworth, especially, in his poetry, uses descriptions of nature to raise the mind to mystic heights. With the advent of the Industrial Revolution, the attitude of people changed – from an awe of nature to a desire to harness everything natural for the benefit of man, which the Romantic poets viewed with concern.

In his poems “The World is Too Much with Us” and “Nutting”, William Wordsworth makes use of the portrayal of the beauties of nature to deplore the greed of man who is mindlessly exploiting nature.

Written in Germany, the poem “Nutting” evokes Wordsworth’s remembrance of turbulent feelings he had when he had gone’ nutting’ as a boy. William Wordsworth writes about a beautiful, pristine wood whose beauty and purity he had destroyed by his greed to gather the nuts .Continuing in the same vein, in “The World is too much with Us”, the poet laments the heartlessness of humankind, which has come under the sway of unfathomable avarice, and which no longer is moved by the beauty of nature.

Wordsworth describes the secret, unexplored place he went to after clambering over rocks and stepping over tangled ferns in “Nutting”. It is a place of perfect peace where the poet’s heart experiences great joy. He describes the nook where he sits down among the flowers under the trees The poem conveys a deep sense of peace and meditation attained by man by connecting with nature. The final lines of the poem convey the spiritual feeling that the beauty of nature inspired in the poet.

The symbolism of the plentiful hazelnut clusters which cover the trees alludes to the bounty of nature. The tattered old clothes the boy wears symbolizes the poverty of the spirit of man. The poet describes how the unsullied nook is ravaged by the violent acts of the boy. Although he is now rich with the nuts he came to gather, he feels a twinge of guilt and pain when he gets a final glimpse of the virgin nook he has destroyed. The symbolism of the earth being exploited mercilessly and violently by man is evident in this poem. He tells us to cultivate a ‘gentleness of heart ‘and exhorts us to be gentle with nature so that we are in harmony with it.

Wordsworth continues to regret the crass, materialistic attitude of man in his Petrarchan sonnet, “The World is too much with us.” He cries out that we waste our resources by consuming too much. He states that we are not in tune with nature any longer as we have become too insensitive. Using the powerful imagery of howling winds which are gathered up like flowers, the poet conveys a sense of urgency in his poem. By portraying the sea as laying bare its bosom to the moon, he alludes to the connectedness of every great and small thing in nature.. He feels angry that the beauty, mystery and force of nature have no effect on the insensitive soul of man, who is out of harmony with nature. The mercenary goals of man disgusts him so much that he wishes he were born as a pagan, who would have had a better communion with the sea and the land.

For Wordsworth, nature is not something to be consumed and exploited, but nature is something that leads man to the universal soul. He makes use of his great descriptive talents to portray that humanity is losing its connected feeling with nature by following the materialistic ideals of getting and spending.’- Essays, UK.

‘We should look beyond economics and open our eyes to beauty’

“We seem to have forgotten that the human spirit is not satisfied by material progress alone. It’s time for us to reconnect with nature.”- Fiona Reynolds, former National Trust director general

“Then, beauty mattered enough to shape policy for the public good. And so after the horror of two world wars, the 1945 government implemented a package of measures designed not only to meet people’s basic human needs but also their spiritual, physical and cultural wellbeing. The designation of National Parks, the protection of our cultural heritage and access to the countryside sat alongside the universal right to education, the NHS and the welfare state.

“We understood then, as we seem to have forgotten now, that the human spirit is not satisfied by material progress alone. As the 19th-century environmentalist John Muir said: “Everybody needs beauty as well as bread.”

“Yet today we seem to have become seduced by what the American economist Albert Jay Nock called “economism”: that which “can build a society which is rich, prosperous, powerful, even one which has a reasonably wide diffusion of material wellbeing. But it cannot build one which is lovely, one which has savour and depth, and which exercises the irresistible power of attraction that loveliness wields.”

Today when we talk about progress we mean only economic progress, and our measure of that is GDP. GDP charts only income, expenditure and production, and doesn’t even try to count the many things that matter but money can’t buy, the things that make us happy, and the natural resources on which we all depend.”…continue to read

Discover more about William Wordsworth: William Wordsworth. 250th anniversary of the poet’s birth

Celebrating the joyous Spring with William Wordsworth

Daffodils At Wordsworth Point, Ullswater

'When William and Dorothy Wordsworth visited Glencoyne Bay on their way back to Grasmere after an overnight stay, it gave William the inspiration to write his most famous poem, - Daffodils. The daffodils are a wild variety and very dainty and neat. The sight of them on a carpet alongside the lake edge is quite spectacular.' Picture by Martin Lawrence Photography

Flowers are blooming, birds are singing, the days are getting brighter. What better way to sing the praises of Spring’s arrival than to read beautiful poetry.

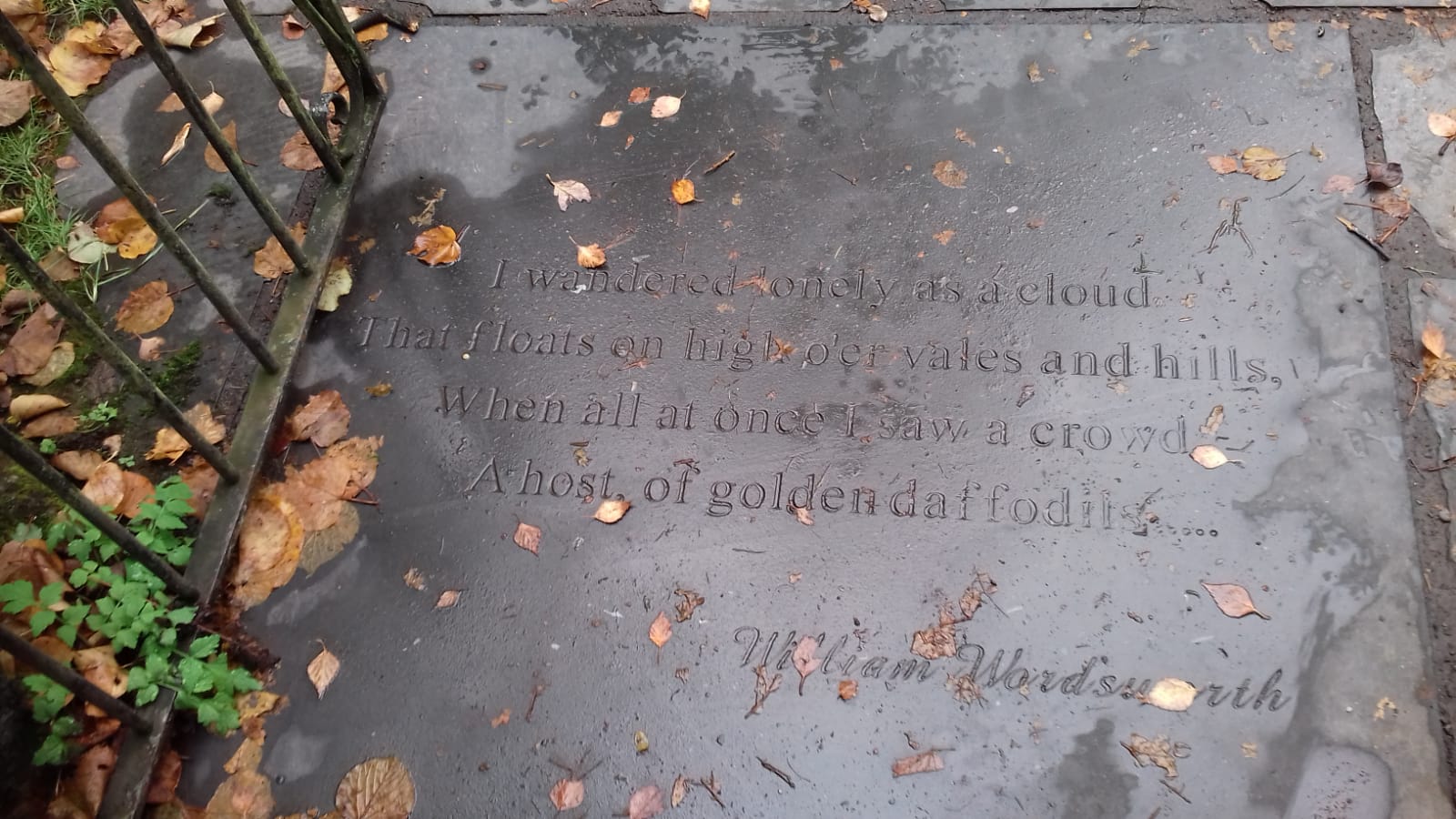

Here is one of my favourite poems I would like to share with you: Of all the famous poems of Wordsworth, none is more famous than "I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud".

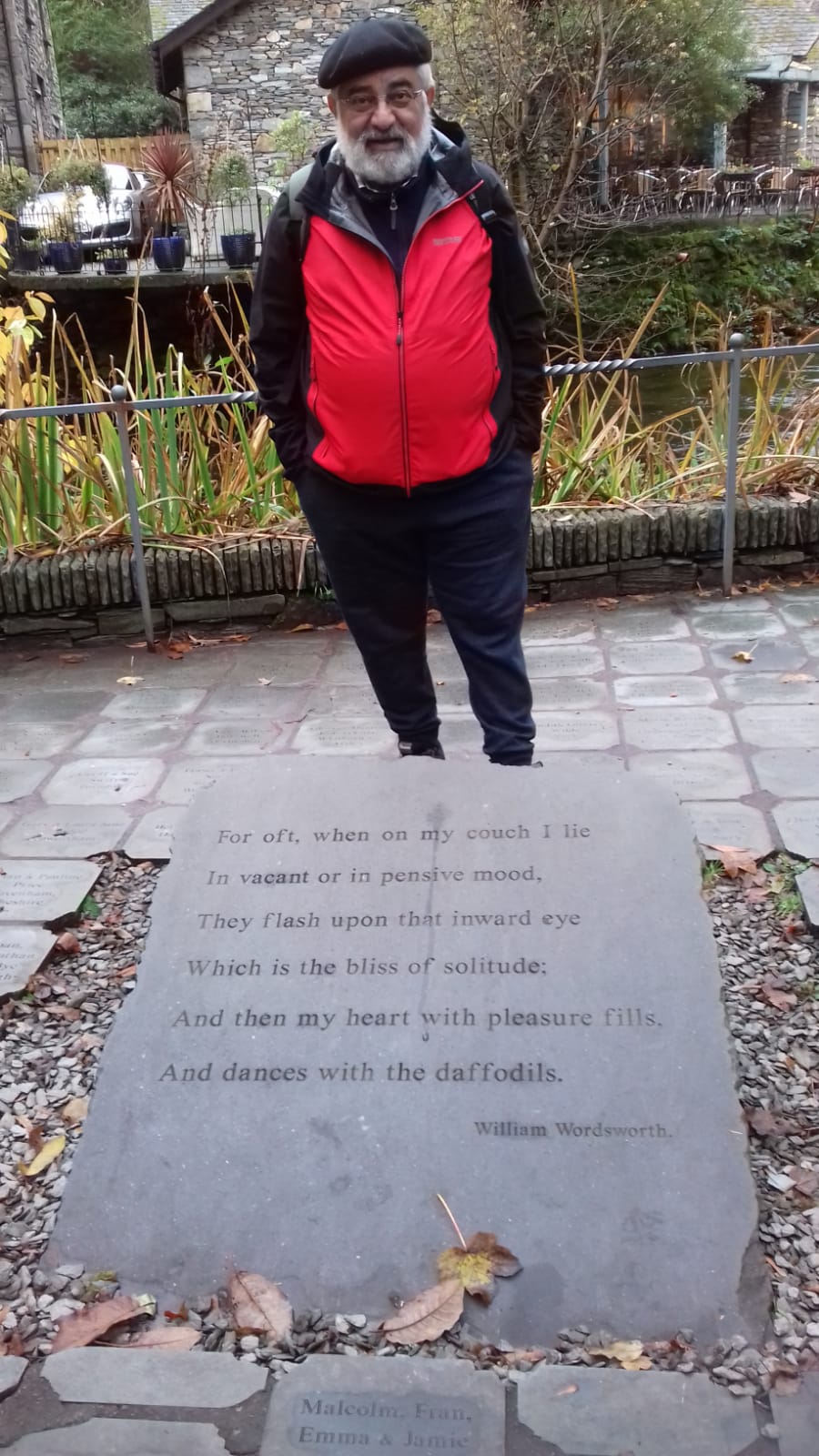

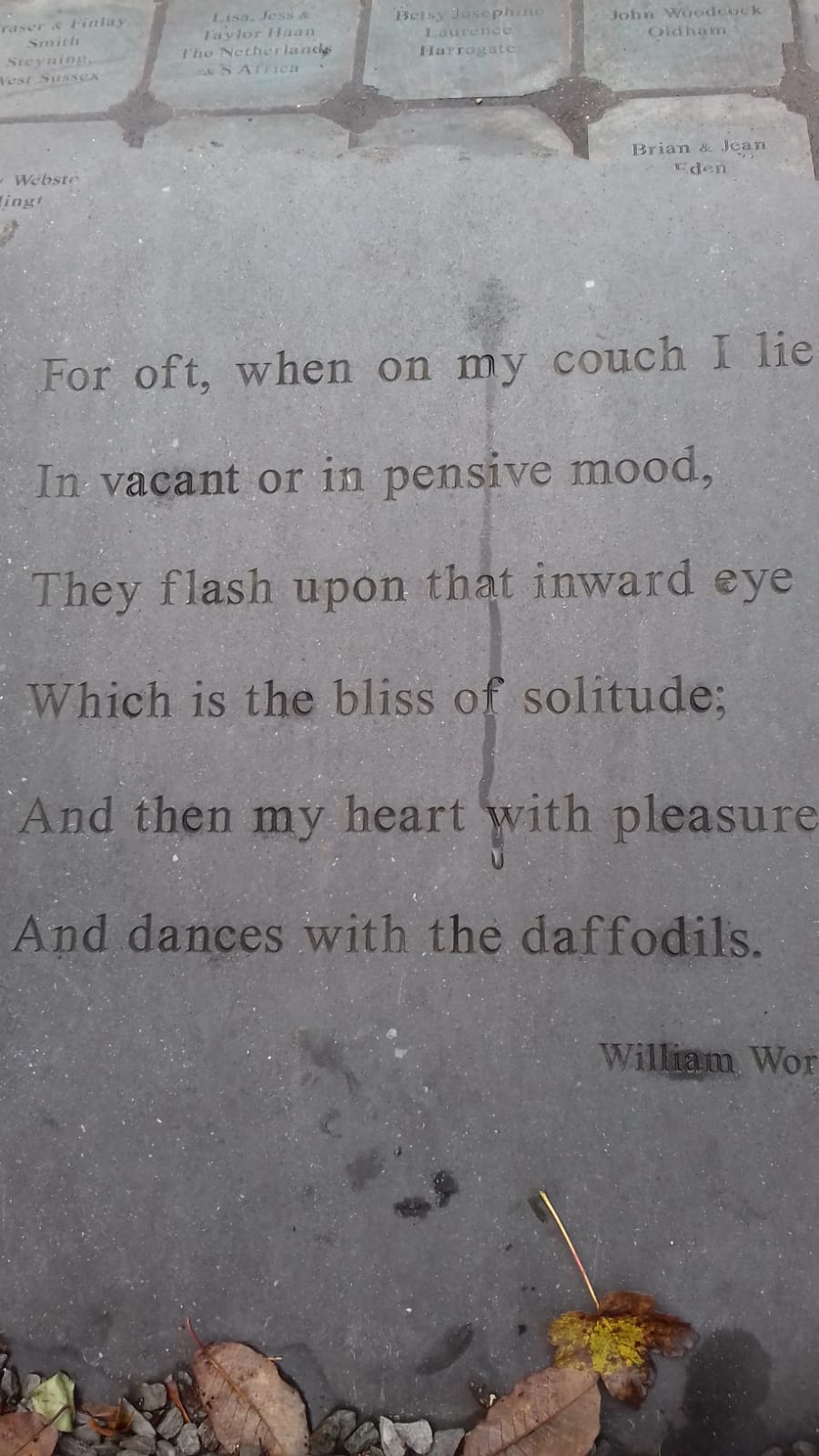

In this poem, Wordsworth says that, wandering like a cloud floating above hills and valleys, he encountered a field of daffodils beside a lake. The dancing, fluttering flowers stretched endlessly along the shore, and though the waves of the lake danced beside the flowers, the daffodils outdid the water in glee. He says that a poet could not help but be happy in such a joyful company of flowers. He says that he stared and stared, but did not realize what wealth the scene would bring him. For now, whenever he feels “vacant” or “pensive,” the memory flashes upon “that inward eye / That is the bliss of solitude,” and his heart fills with pleasure, “and dances with the daffodils.”

I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud

I wandered lonely as a cloud

That floats on high o'er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host, of golden daffodils;

Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

Continuous as the stars that shine

And twinkle on the milky way,

They stretched in never-ending line

Along the margin of a bay:

Ten thousand saw I at a glance,

Tossing their heads in sprightly dance.

The waves beside them danced; but they

Out-did the sparkling waves in glee:

A poet could not but be gay,

In such a jocund company:

I gazed—and gazed—but little thought

What wealth the show to me had brought:

For oft, when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude;

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the daffodils.

The healing power of images in Wordsworth

‘At the beginning of the nineteenth century, William Wordsworth, who was keenly interested in psychology, began looking into the power of images to heal psychological damage. His quest was quite personal, in fact it was a matter of life and death to him. Like many young English people in his generation he was suffering from profound despair in the aftermath of the French Revolution. He had lost his idealism and hope, and much more; his lover and their daughter. He’d been forced to return to leave them behind and return to an England that was quite depressing, for it was having a conservative reaction to the events that had inspired so many young people.

He was in despair but he found a great source of healing in natural images. A great poet, he was also highly attuned to the beauty of natural settings: mountains, woods, lakes, in his rural Cumberland had stirred him from his childhood on. In learning to write a whole new kind of poetry – that stood in stark contrast to the more rationalistic conservative verse he was raised on, he began writing experimentally with close companions, his sister Dorothy and the poet Coleridge. In these poems he discovered a special value in certain images. These were memories that stayed with him, and that he “recollected in tranquility”. Often the recollection took place in a crowded city, far from the natural setting of his native lake district. By contemplating these “restorative images” – as he called them, he found he could heal the “impaired imagination.”

Wordsworth was primarily interested in images that came to him from remembering certain dramatic scenes. The actual events that he recalled were not necessarily full of positive feeling. In many cases in fact they were strange, foreboding, disturbing. Yet oddly by contemplating these difficult memories later, he found great healing. He called these special moments “spots of time” and in his long autobiographical poem, The Prelude gave several examples of these events that had for him a healing property. Wordsworth’s emphasis on “restorative images” offers a second testimony to the healing power of images I find in dreams. Dreams also offer “spots of time”, poetic moments I call “events”. By contemplating the “events” in dreams, we can also heal the “impaired imagination”.- The healing power of images in Wordsworth

William Wordsworth Life and Journey in Pictures

Born in Cockermouth

Photo:visitcumbria.com

Wordsworth's Birthplace, Cockermouth House

Wordsworth was born in a grand, terracotta-coloured house on Cockermouth’s Main Street

that’s now a National Trust museum.-Photo: National Trust

Hawkshead and Ambleside

Wordsworth’s grammar school in Hawkshead. Photo: Phoebe Taplin via The Guardian

Hawkshead Grammar School with its mullioned windows and sundial over the door, is where Wordsworth went from age eight. The names of Wordsworth and his fellow students can still be seen scratched on the wooden desks. There’s a memorial to Wordsworth’s old teacher in the sturdy stone church above it, and on a cobbled alley, round the corner from the little Beatrix Potter Gallery is Ann Tyson’s cottage, where Wordsworth stayed.

Home at Grasmere

Grasmere and Grasmere Village from Loughrigg. Picture by Tony Richards.

In 1799, William Wordsworth fell in love with Dove Cottage and Grasmere whilst on a walking tour of the Lake District. Within a few months, he had set up home here in the hamlet of Town End with his sister Dorothy. It was whilst living here that Wordsworth produced the most famous and best-loved of his poems and Dorothy wrote her fascinating Grasmere journal.

Dove Cottage, the place where poetry changed forever.

Photo:visitcumbria.com

‘Embrace me then, ye Hills, and close me in;

Now in the clear and open day I feel

Your guardianship; I take it to my heart;

‘Tis like the solemn shelter of the night.

But I would call thee beautiful, for mild,

And soft, and gay, and beautiful thou art

Dear Valley, having in thy face a smile

Though peaceful, full of gladness. Thou art pleased,

Pleased with thy crags and woody steeps, thy Lake,

Its one green island and its winding shores;

The multitude of little rocky hills,

Thy Church and cottages of mountain stone

Clustered like stars some few, but single most,

And lurking dimly in their shy retreats,

Or glancing at each other cheerful looks

Like separated stars with clouds between.’

– William Wordsworth, 'Home at Grasmere'

Rydal Mount and its gardens, originally designed by the poet William Wordsworth

‘Wordsworth perfected his most famous lines in the delightfully romantic garden he created in the Lake District.’

‘Had William Wordsworth not been a poet, he could have earned his living as a landscape gardener, says Peter Elkington, curator of Rydal Mount, the house in the Lake District that was Wordsworth’s family home for nearly half his life.

It was here that he revised his famous poem Daffodils... They were no longer a host of ‘dancing’ daffodils, as he originally wrote in his 1804 version, but a host of ‘golden’ daffodils, ‘fluttering and dancing in the breeze’.- Read more

Sunset view of Rydal Water, Cumbria. Photo: Phoebe Taplin via The Guardian

Ullswater

Photo:visitbritainshop.com

‘Wander lonely as a cloud along the shore where Wordsworth saw his dancing lakeside daffs. The bracken-cloaked mountains round tranquil Ullswater run down to the water’s edge, and the woods near Glencoyne still fill with flowers each spring. Follow the daffodil waymarking of the Ullswater Way, opened in 2016, past ferny woods to Aira Force waterfall and catch the steamer down the lake to Glenridding. ‘

St John’s College, Cambridge

Punt on the Cam at St John’s College, Cambridge. Photo: Phoebe Taplin via The Guardian

‘Wordsworth’s first home outside the Lake District was St John’s, Cambridge. In his autobiographical poem The Prelude, he recalls crossing the River Cam and seeing, as he arrived in 1787, the turrets and pinnacles on “the long-roofed chapel of King’s College”.

Coleridge Cottage, Somerset

Photo:pinterest.co.uk

‘Wordsworth's friend, and co-creator of 1798 collection Lyrical Ballads, Samuel Taylor Coleridge lived in a tiny 17th-century cottage in Nether Stowey from 1797. William and Dorothy Wordsworth lived at the recently rescued Alfoxton , a big house five miles away, and together the friends explored the heathery Quantock hills and rocky coast. For walkers, there’s now the 50-mile Coleridge Way, signposted with quill symbols.’

Tintern Abbey, Monmouthshire

Photo:theguardian.com

‘This towering roofless medieval church on the banks of the Wye – its graceful arches a perfect focal point among steep riverside woods – is one of Wordsworth’s best-known destinations. The poem that helped make it famous doesn’t actually mention Tintern after the title, but explores the evocative, life-affirming power of “a wild secluded scene”...’

Westminster Bridge, London

London then: The bridge William Wordsworth visited in 1802 was replaced in 1862. Painting by Joseph Farrington, 1789.

Credit: Stephen C. Dickson/Wikimedia Commons

Composed upon Westminster Bridge, September 3, 1802

‘Earth has not any thing to show more fair:

Dull would he be of soul who could pass by

A sight so touching in its majesty:

This City now doth, like a garment, wear

The beauty of the morning; silent, bare,

Ships, towers, domes, theatres, and temples lie

Open unto the fields, and to the sky;

All bright and glittering in the smokeless air.

Never did sun more beautifully steep

In his first splendour, valley, rock, or hill;

Ne'er saw I, never felt, a calm so deep!

'The British Library near Euston has a small but engrossing free display of letters, books and pictures to celebrate Wordsworth’s anniversary. It includes a manuscript draft of his poem “Composed on Westminster Bridge”. In July 1802, Wordsworth crossed the bridge on a coach from Charing Cross, heading for Calais to meet his lover Annette Vallon and their daughter . London’s “Ships, towers, domes, theatres and temples” at sunrise prompted one of the poet’s best-loved sonnets, beginning: “Earth has not anything to show more fair…” Nearby, Westminster Abbey has a memorial to Wordsworth in Poet’s Corner, with the marble poet composing on a plinth carved with ferns and daisies, and a bust of Coleridge above his head.’

Chatsworth, Derbyshire

Photo:theguardian.com

‘In 1830 Wordsworth took a walking holiday in Derbyshire with Dorothy and wrote a sonnet about Chatsworth House , contrasting the “stately mansion” with cottages in the “wild Peak”...’ Poet’s corners: a car-free tour of inspiring Wordsworth sites

St Oswald’s Church, Grasmere: The final resting place of Wordsworth and his family

Grasmere Church, dedicated to St. Oswald the Northumbrian King,

stands on the bank of the River Rothay.-Photo:grasmerevillage.com

The oldest part of the present church is thought to have dated from the twelfth or thirteenth century. Wordsworth who used to live in the Rectory at Grasmere at one time describes the church in his poem “The Excursion”:

“Not raised in nice proportions, was the Pile,

But large and massy, for duration built,

With pillars crowded and the roof upheld,

By naked rafters intricately crossed”

St Oswald’s Churchyard.- Photo:grasmerevillage.com

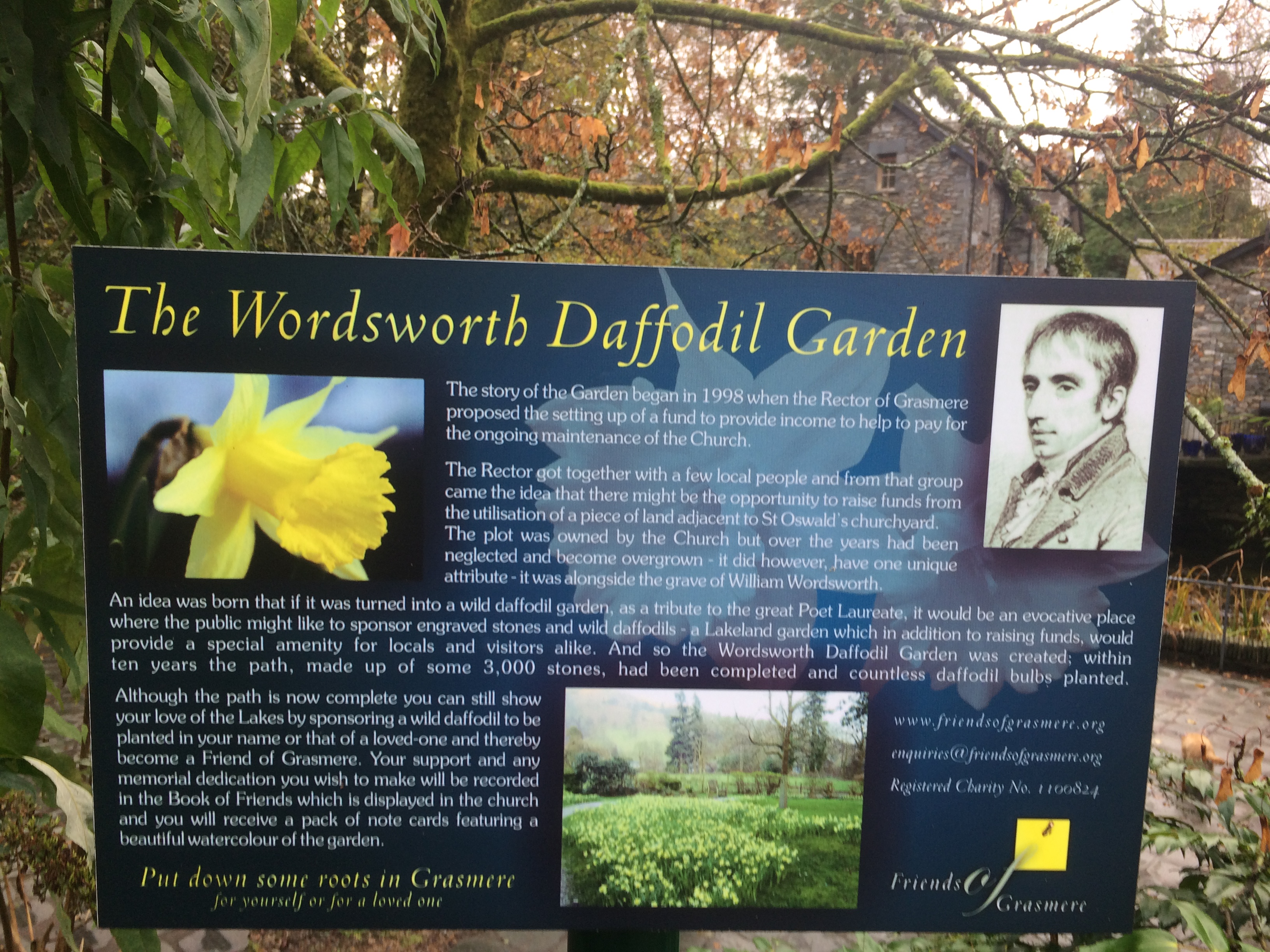

St Oswald’s Daffodil Garden. Photo:inspirock.com

‘William Wordsworth is buried in the churchyard in the centre of Grasmere village. The Church is named after St Oswald, a 7th Century Christian King of Northumberland, who is said to have preached on this site. It is the parish church of Grasmere, Rydal and Langdale, and each township has its own separate gate into the churchyard.

The 13th century nave holds several memorials, including several to the Le Fleming family of Rydal Hall, but the one most people come to see is that of William Wordsworth. The North aisle, almost as big as the nave, was added in 1490 for the residents of Langdale.’

Photo:where2walk.co.uk

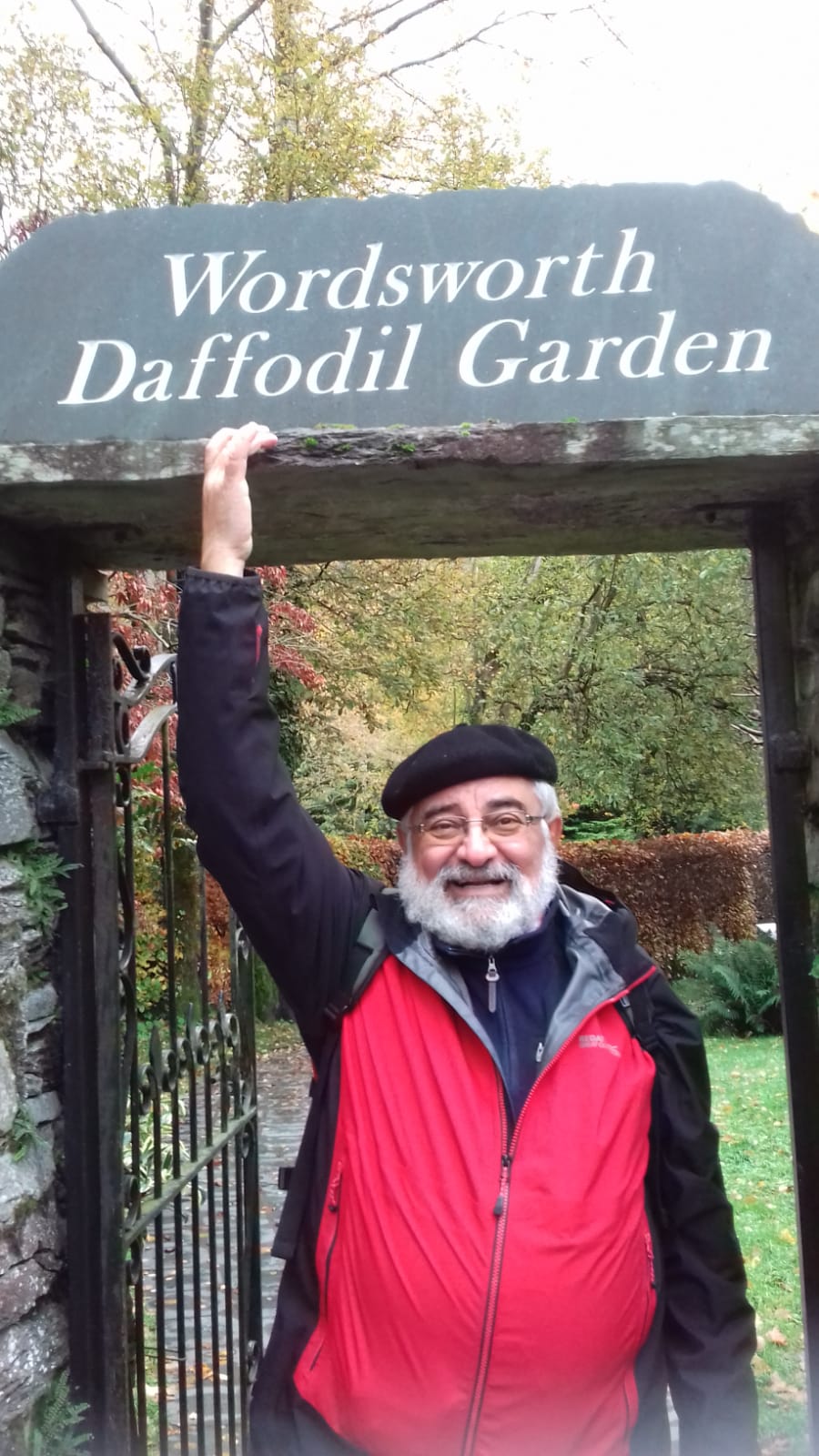

In the footsteps of my wise teacher

Walking and Wandering with Wordsworth in the Lake District

31 October- 8 November 2019

Not all of us can write like poets, but at least we can go on some of the same walks as England's greatest.

Kamran and Annie Mofid: Our Picture Gallery-- A picture is worth a thousand words

Photos Credits: Kamran and Annie Mofid