Allen Bennett

Photo:theguardian.com

Alan Bennett, the playwright and passionate champion of the underdog, has turned his fire on the creeping privatisation of Britain’s public institutions.

The 80-year-old writer used a “sermon” at Cambridge University to lambast what he said was the pursuit of profit in public services from prisons to the National Health Service, and suggested the drivers of privatisation were comparable to the “devout louts” of 17th Century puritanism.

In a broad-ranging sermon before the university, Bennett criticised the lack of fairness in British society encapsulated by the private school system, recalling his own visit to Cambridge in the 1950s with “the odds stacked against me” as he sought a scholarship against public school-educated rivals.

Private Education is unfair and un-Christian

‘But if, unlike the Daily Mail, one believes that the nation is still generous, magnanimous and above all fair, it is hard not to think that we all know that to educate not according to ability but according to the social situation of the parents is both wrong and a waste.

Private education is not fair. Those who provide it know it. Those who pay for it know it. Those who have to sacrifice in order to purchase it know it. And those who receive it know it, or should. And if their education ends without it dawning on them then that education has been wasted. I would also suggest – hesitantly, as I am not adept enough to follow the ethical arguments involved – that if it is not fair, then maybe it's not Christian either.

How much our ideas of fairness owe to Christianity, I am not sure. Souls, after all, are equal in the sight of God and thus deserving of what these days is called a level playing field.

This is certainly not the case in education and never has been, but that doesn't mean we shouldn't go on trying. Isn't it time we made a proper start? Unlike today's ideologues, whom I would call single-minded if mind came into it at all, I have no fear of the state. I was educated at the expense of the state, both at school and university. My father's life was saved by the state as, on one occasion, was my own. This would be the nanny state, a sneering appellation that gets short shrift with me. Without the state, I would not be standing here today.

I have no time for the ideology masquerading as pragmatism that would strip the state of its benevolent functions and make them occasions for profit. And why roll back the state only to be rolled over by the corporate entities that have been allowed, nay encouraged, to take its place? I am uneasy when prisons are run for profit or health services either. The rewards of probation and the alleviation of suffering are human profits and nothing to do with balance sheets. And these days no institution is immune. In my last play, the Church of England is planning to sell off Winchester Cathedral.

"Why not?" says a character. "The school is private, why shouldn't the cathedral be also?" And it's a joke, but it's no longer far-fetched.

With ideology masquerading as pragmatism, profit is now the sole yardstick against which all our institutions must be measured, a policy that comes not from experience but from assumptions – false assumptions – about human nature, with greed and self-interest taken to be its only reliable attributes.

In pursuit of profit, the state and all that goes with it is sold from under us who are its rightful owners and with a frenzy and dedication that call up memories of an earlier iconoclasm.

Which brings me nearly to the end.

One pastime I had as a boy which, thanks to my partner, I resumed in middle age, was looking at old churches, "ruin-bibbing" Larkin dismissively called it, though we perhaps have a little more expertise than Larkin disingenuously claimed he had. I do know what rood lofts were, for instance, though, like Larkin, I'm not always able to date a roof.

The charm of most medieval churches consists in what history has left and one learns to delight in little, the dregs of history: a few 15th-century bench ends, an alabaster tomb chest or, where glass is concerned, just the leavings of bigotry, with ideology weakening when it came to out-of-reach tracery – the hammer too heavy, the ladder too short – so that only fragments survive, a cluster of crockets and towers maybe, the glimpse of a golden city with a devil leering down.

In my bleaker moments, these shards of history seem to me emblematic obviously of what has happened to England in the past, but also a reminder and a warning of what in other respects is continuing to happen in the present, with the fabric of the state and the welfare state in particular stealthily dismantled as once the fabric of churches more rudely was, sold off, farmed out; another Dissolution, with profit taking precedence over any other consideration, and the perpetrators today as locked into their ideology and convinced of their own rightness as any of the devout louts who four and five hundred years ago stove in the windows and scratched out the faces of the saints as a passport to Heaven.

I end with the last few lines of my first play, Forty Years On. It's set in a school with the headmaster on the verge of retirement and is what nowadays is called a play for England. It ends with the boys and staff singing the doxology "All Creatures That on Earth Do Dwell", with before it, this advertisement for England:

To let. A valuable site at the crossroads of the world. At present on offer to corporate clients. Outlying portions of the estate already disposed of to sitting tenants. Of some historical and period interest. Some alterations and improvements necessary.’

On the issues raised above see more:

Alan Bennett launches fierce attack on private education

Why Alan Bennett's plea for the reform of private education is welcome

Abolish private schools, Alan Bennett argues

“The charge sheet is this. The government is led by a clique of toffs who have neither respect for their colleagues, nor empathy with the average voter. Their born-to-rule mentality means they have a greatly over-inflated view of their own capabilities, which deafens their ears to the advice and warnings of others who might actually know better. They are nothing like as good at governing as they think they are. And this, the charge sheet concludes, is now inflicting serious harm on both the country and the Conservatives' future electoral prospects. This view is now becoming more and more prevalent in the media, too, even among the press that the Conservatives would normally count as their friends.”-Andrew Rawnsley, The Observer, 29 April 2012

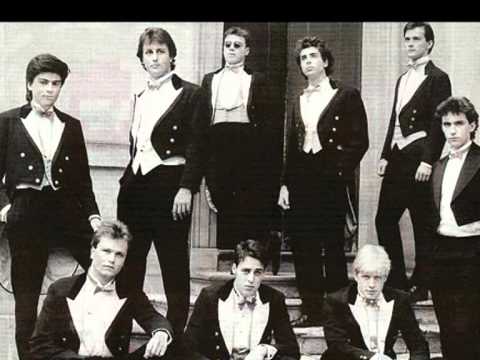

Men of the people? David Cameron and Boris Johnson in the livery of the Oxford University Bullingdon Club