- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 11293

An earlier version of this Blog was published on 5 August 2023

World in Chaos and Despair: Remembering the Lessons of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

‘My God, what have we done?’-The timeless and chilling words of Captain Robert Lewis, the co-pilot of a B-29 bomber – named Enola Gay, who dropped the 4,400kg atomic bomb, called Little Boy, on Hiroshima still echo 80 years on.

The wrecked framework of the Museum of Science and Industry as it appeared shortly after the blast.

City officials recently decided to preserve this building as a memorial though

they had at first planned to rebuild it. (Bettmann / Getty)/The Atlantic

On August 6, 1945, for the first time ever in human history an atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. August 6, 2025, marks the 80th year since this sheer wanton act of vandalism against humanity, which was repeated three days later, on Nagasaki.

“Tragedy exerts its hold upon our imaginations because it reminds us that justice is an illusion. Hiroshima is the great tragedy of our age from which we continue to seek understanding and yet can never understand.”- Richard Flanagan, author of Question 7

Marking 80 years since the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Remembering the lives that were lost and the cities that were destroyed in egregious acts against humanity

August 6, 1945 8:15am Hiroshima

August 9, 1945 11.02am Nagasaki

In memory of the people who perished in the 1945 atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, I ask all the friends of the Globalisation for the Common Good Initiative to hold a one-minute silent prayer and to light a candle to remember the victims and to pray for the realisation of lasting world peace, free from the weapons of mass destruction.

Photo credit: via Wikipedia

On 6 August 1945, the United States dropped the first ever Atomic Bomb, nicknamed the Little Boy, on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. In a single moment this bombing claimed the lives of 140,000 people, and turned over 4 square miles of the city into dust. Tens of thousands more eventually died and are still dying prematurely due to radiation and other consequences. All that remains since that notoriously evil day is the Genbaku Dome, or what is more commonly referred to as the “A-bomb Dome.” Days after the Hiroshima attack, Nagasaki was similarly destroyed by another bomb, nicknamed the Fat Man, which killed 74,000 people with the same horrific pain and consequences as the one in Hiroshima.

Let us remember the lives that have been lost, maimed and injured, as well as the cities that were destroyed in the egregious acts against humanity, and strive for a nuclear free world to honour the legacy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Sunrise at the Atomic Bomb Dome in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, 6 August 2019. Photo: theguardian.com

We must never ever forget the legacy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the lessons that are at risk of being forgotten by many around the world, including the world political leaders today.

To highlight this point, suffice to note the recent decision by the UK government to totally forget the tragic lessons of Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, and instead to increase the number of nuclear warheads in its arsenal, for the first time since the cold war, by over 40 per cent. The UK will now have 260 warheads; each 10 times deadlier than Hiroshima.

This tragic and foolish decision was taken despite the UK being a signatory to the UN’s Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), which requires that we should be working towards disarmament, and are committed under international law to “pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament” (Article VI).

The above highlights the urgency and the necesity of the need for the progressive and concerned citizens around the world to continue and indeed, campain harder against further nuclearisation and warmongering. We have a duty and responsibility to remember the victims of the bombing, the consequent destruction, the everlasting pain and misery of the survivors to campaign for world peace, justice and nuclear disarmament, creating much-needed awareness about the danger nuclear weapons pose to the very future of humanity. Carpe diem!

MAY PEACE PREVAIL ON EARTH

Photo:A man lights incense in Hiroshima, 6 August 2019. theguardian.com

“Although the people living across the ocean surrounding us are all our brothers and sisters why, Oh Lord, is there trouble in this world? Why do winds and waves rise in the ocean surrounding us? I earnestly wish the wind will soon blow away all the clouds hanging over the tops of the mountains.”- Shinto Peace Prayer

"When the Eagle of the North gets together with the Condor of the South, it is time for all the Rainbow Tribes of the World to get together and bring Peace upon this world."- Native American Prophecy

"We're all one family, all together, We human beings, all one big mob!"- Miriwoong, Australian Aboriginal

Lord, make me an instrument of your peace,

Where there is hatred, let me sow love;

where there is injury, pardon;

where there is doubt, faith;

where there is despair, hope;

where there is darkness, light;

where there is sadness, joy;

O Master, grant that I may not seek so much to be consoled as to console;

to be understood as to understand;

to be loved as to love.

For it is in giving that we receive;

it is in pardoning that we are pardoned;

and it is in dying that we are born to eternal life- Prayer of Saint Francis of Assisi

Deep Peace of the running wave to you

Deep Peace of the flowing air to you

Deep Peace of the quiet earth to you

Deep Peace of the shining stars to you

Deep peace of the shades of night to you

Moon and stars always giving Light to you- Celtic Peace Prayer from Antiquity

On this day I also wish to remember my own visit to Hiroshima in July 1995 and to

recall Japan’s Ambassador’s Visit to Coventry, 28 Years On.

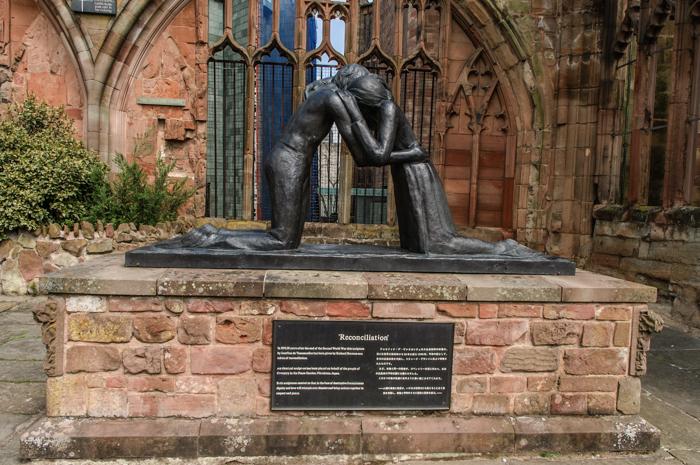

Coventry Cathedral-Statue of Reconciliation

In the mid 1990s, I had founded the Centre for the Study of Forgiveness and Reconciliation at Coventry University. This was the culmination of my years of cooperation with Coventry Cathedral and the City of Coventry.

To commemorate the 50th Anniversary of the ending of the war between Japan and Europe, at the suggestion of Coventry Cathedral’s Provost, John Petty, Sir Richard Branson had funded the construction of two replicas of the original Statue of Reconciliation (by sculptress, Josefina de Vasconcello, installed first at the School of Peace Studies at Bradford University) one for the ruins of Coventry Cathedral and the other for Hiroshima Peace Park.

I was honoured to be present for the installation ceremony at Coventry Cathedral in 1995. Then, at the personal invitation of Sir Richard, I accompanied him and the Coventry delegation, the Lord Mayor, Provost John Petty, Canon Paul Oestreicher, and others to Hiroshima for the unveiling ceremony of the Statue at Hiroshima Peace Museum.

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, 1995, on the right of the picture, Coventry Cathedral delegation (Canon Paul Oestreicher and Provost John Petty) and myself(Kamran Mofid). Photographer: Unknown

I am most grateful for that opportunity which I will remember forever.

A bit more on "My Coventry Story":

“...We also together - in association with and support of the University, the Cathedral and the City Council - instigated and co-founded the Centre for the Study of Forgiveness and Reconciliation at Coventry University and as part of its work, in association with the Ambassadors’ Lecture Series, which we had founded already, invited international speakers including the former presidents of Ireland and South Africa, namely, Mrs. Mary Robinson, and F.W. de Klerk to deliver lectures at Coventry Cathedral. Moreover, we also invited other international speakers including Ambassadors of Japan, Germany, Italy, Egypt, Mexico and the High Commissioner of Canada to deliver lectures on the need for dialogue and mutual respect among different cultures and civilisations at Coventry’s St. Mary’s Guildhall. We were delighted when Mrs. Robinson accepted our invitation to become the Patron of our newly founded Centre. Our joint activities resulted in many publications. At George’s suggestion and with the kind support of Canon Paul Oestreicher and Provost John Petty, I received an invitation from Sir Richard Branson to accompany the Coventry delegation (City and Cathedral) to Hiroshima for the unveiling ceremony of the Statue of Reconciliation at Hiroshima Peace Park...”- The story of a boy from Iran who became a man in Coventry

The Western World and Japan by His Excellency Hiroaki Fujii, Coventry, 1995

78 Years on A Message of Hope from Hiroshima

A Selection of Must-read books

The Hiroshima Men: The Quest to Build the Atomic Bomb, and the Fateful Decision to Use It

‘At 8:15 a.m. on August 6th, 1945, the Japanese port city of Hiroshima was struck by the world's first atomic bomb. Built in the US by the top-secret Manhattan Project and delivered by a B-29 Superfortress, a revolutionary long-range bomber, the weapon destroyed large swaths of the city, instantly killing tens of thousands. The world would never be the same again.

The Hiroshima Men's unique narrative recounts the decade-long journey towards this first atomic attack. It charts the race for nuclear technology before, and during the Second World War, as the allies fought the axis powers in Europe, North Africa, China, and across the vastness of the Pacific, and is seen through the experiences of several key characters: General Leslie Groves, leader of the Manhattan Project alongside Robert Oppenheimer; pioneering Army Air Force bomber pilot Colonel Paul Tibbets II; the mayor of Hiroshima, Senkichi Awaya, who would die alongside over eighty-thousand of his fellow citizens; and Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist John Hersey, who travelled to post-war Japan to expose the devastation the bomb had inflicted upon the city, and in a historic New Yorker article, described in unflinching detail the dangers posed by its deadly after-effect, radiation poisoning.

This thrilling account takes the reader from the corridors of the White House to the laboratories and test sites of New Mexico; from the air war above Nazi Germany and the savage reconquest of the Pacific to the deadly firebombing air raids across the Japanese Home Islands. The Hiroshima Men also includes Japanese perspectives - a vital aspect often missing from Western narratives - to complete MacGregor's nuanced, deeply human account of the bombing's meaning and aftermath.’- Buy the book HERE

Hiroshima

‘The explosion over Hiroshima of the first nuclear bomb reduced, in an instant, an entire city to rubble and killed over 100,000 men, women and children. It also announced a new era in human history: the Atomic Age.

Written only a year after the event, John Hersey's Hiroshima was an immediate phenomenon. Originally published in the New Yorker magazine - the only single article to ever fill an entire edition - it quickly became a bestseller and established itself as the definitive account of the bombing. Hersey's lucid prose and focus on eye-witness experience made plain the horror of nuclear weapons, clearly demonstrating the incredible danger this new technology posed to humanity.

This edition includes an additional chapter, written forty after Hiroshima was first published, exploring the devastating long-term effects of the bomb on survivors, as well as how a city can begin to rebuild after such a catastrophe.’-Buy the book HERE

Rain of Ruin: Tokyo, Hiroshima and the Surrender of Japan

‘In the closing months of the Second World War hundreds of thousands of Japanese, mostly civilians, died in a final outburst of violence from the air. American planes were beginning to run low on plausible targets when it was decided to use two atomic weapons in a final, terrible flourish to try to end the war.

Richard Overy’s remarkable new book rethinks how we should regard this last stage of the war and the role of the bombing. This book explores the way in which the willingness to kill civilians and destroy cities became normalized in the course of a horrific war as moral concerns were blunted and scientists, airmen, and politicians followed a strategy of mass destruction they would never have endorsed before the war began. But it also engages with the new scholarship that shows how complex the effort to end the war was in Japan, where ‘surrender’ was entirely foreign to Japanese culture.’- Buy the book HERE

Question 7

‘By way of H. G. Wells and Rebecca West’s affair, through 1930s nuclear physics, to Flanagan’s father working as a slave labourer near Hiroshima, this chain of events culminates in a young man finding himself trapped in a rapid on a wild river, not knowing if he is to live or to die…’-Buy the book HERE

See also:

Green Legacy of Hiroshima- Spreading Seeds of Hope and Peace All Over the World

Journey to Healing: Let Me Know What is Essential

GCGI is our journey of hope and the sweet fruit of a labour of love. It is free to access, and it is ad-free too. We spend hundreds of hours, volunteering our labour and time, spreading the word about what is good and what matters most. If you think that's a worthy mission, as we do—one with powerful leverage to make the world a better place—then, please consider offering your moral and spiritual support by joining our circle of friends, spreading the word about the GCGI and forwarding the website to all those who may be interested.

Hiroshima the City of Hope

Photo:metropolisjapan.com

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 8674

First published on 03 December 2012

N.B. {This “thought sheet”, harvesting the fruits of contemplation, is offered as a contribution to the public conversation about values and the shaping of the social ethos in which we live: Our moral compass, if you will}. This is how I had begun my speech at the Antalya Forum in 2012. My words, sentiments and offerings ring as true today as they did then. The timeless question remains: Will We Ever Learn?

Antalya Forum, “Rethinking the Global Economic Order”

29 November-2 December 2012, Antalya, Turkey

Beyond the Wasteland: Seven Common Good Steps to Build a Compassionate World

A Presentation by

Prof. Kamran Mofid, Founder, Globalisation for the Common Good Initiative, UK*

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 1022

Healing begins with love, remembering, and speaking truth to power and believing that change is possible.

The power of Amazonian spirituality and truth-telling to heal mother nature

Amazon rainforest in Brazil. PhotoSpirit/Alamyvia The Guardian

'To be a person is to have a story to tell.'

‘Stories, because of their imaginative power which engages the brain, have much greater impact than simple facts. Increased brain engagement leads not only to increased thought on the engaging topic, but increased memory as well. When that engagement and memory are controlled and focused in a positive way, the brain’s love for storytelling can be the key to healing and happiness.’-Greater Good Magazine

- From Cyrus to Ayatollahs: Four Thousand Years of Persian-Jewish Relation

- My Poem of the Month: June is the Month of Summer Solstice, Dreams, Love, Romance and Marriage

- A Poem on Hope: Embracing Place and Possibility

- A reflection on the healing and heart touching words and poems of Iranian American poet Kaveh Akbar

- Empathy is the sign of Strength not Weakness: The Legacy of a Good, Kind and Caring Leader