- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 1638

Sir Paul Nurse FRS, Director, Francis Crick Institute

'Paul Nurse is a geneticist and cell biologist who has worked on how the eukaryotic cell cycle is controlled. His major work has been on the cyclin dependent protein kinases and how they regulate cell reproduction. He is Director of the Francis Crick Institute in London, and has served as President of the Royal Society, Chief Executive of Cancer Research UK and President of Rockefeller University.

He shared the 2001 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine and has received the Albert Lasker Award, the Gairdner Award, the Louis Jeantet Prize and the Royal Society's Royal and Copley Medals. He was knighted in 1999, received the Legion d'honneur in 2003 from France, and the Order of the Rising Sun in 2018 from Japan. He served for 15 years on the Council of Science and Technology, advising the Prime Minister and Cabinet, and is presently a Chief Scientific Advisor for the European Union and a trustee of the British Museum'.-Photo: The Francis Crick Institute

Sir Paul in conversation with Andrew Anthony , The Observer*

The Nobel prize-winning scientist on Covid-19, the burden of Brexit, his astonishing upbringing and terrible failures at French

Your book is a reminder of the fundamental importance of cells. Do you think cells have been overshadowed by genes in the public imagination?

I’m a geneticist, so I’ve lived through molecular genetics and molecular biology and that has focused a lot on genes. I do think cells have not caught the attention of the world in perhaps the way they should have done, because it’s the fundamental unit of life. I sometimes use this analogy: it’s like biology’s atom. It’s not the gene, it’s the cell.

During the Covid-19 crisis, you’ve been critical of ministers and advisers, comparing them to blancmange. Do you think we need to rethink that relationship between politicians and advisers?

Yes, I do. I’m particularly concerned about the attempt to convey communication through one-liners such as “we’re following the science”. It’s a sort of populist tendency and that reduces complex situations to an almost meaningless sentence. I also think we need more clarity about how decisions are made. For example, testing for coronavirus was absolutely critical. What they decided to do was produce very big labs to do it, not thinking that this would take many months to get it to work efficiently. Whereas they could have developed it locally and contributed something immediately. All the testing capacity basically did nothing during the big infection phase. That was very bad policy and implemented badly, but we didn’t see the discussions behind those decisions.

Another area of concern for you is the effect of Brexit on the science community. Do you see any cause for optimism there?

Not really. There are three major science blocs in the world, which are North America, China and the far east and Europe. Britain is actually good at science and had a lot of influence in European science. And so we have lost power and influence. That’s a political thing. The psychological thing is that I meet scientific colleagues around the world and they just think that the UK has turned away from collaborative science by looking back on an imperial history that no longer exists. It’s just very sentimental. And we’ve taken a leap several decades into the past.

You mention an extraordinary personal story in the book: that you found out that your sister was actually your mother. How has it affected your sense of identity?

I was in my late 50s when I found out. I was living in New York and I was president of a research university called Rockefeller University. I applied for a green card and was turned down, which was a bit of a surprise because I had a Nobel prize, I was president of a university and I was knighted. It was because they didn’t like my birth certificate, which didn’t name my parents. So I applied for a full birth certificate and discovered the truth. I’m astonished that my parents, who were my grandparents, managed to keep this all quiet. As my actual mother and grandparents were dead, I had no recourse to find out exactly what happened. I would like to know who my father is. I mean, I’m a geneticist. I’m actually quite a good geneticist. And I lived for half a century not knowing my own genetics. I hope I find out before I eventually die.

Your main area of research is in yeast, but you became head of Cancer Research UK. How far away do you think science is from gaining some cellular grip on cancer?

Our understanding of cancer has really dramatically improved. We understand the cellular basis of it, the genetic origins of it, the ways in which it’s caused, the way in which the regulatory circuits get altered in cancer cell tissue, which is immensely complicated and one reason it’s so difficult to develop therapies. Our treatment of it is still lagging but in my view we will be able to get cancer under significantly more control in a matter of decades, though we’ll never be able to eliminate it.

You famously failed your French O-level six times. What are your linguistic skills like these days?

They are absolutely appallingly bad. It’s a matter of great distress to me because I travel a great deal. I even got a Légion d’honneur, believe it or not. I had to give the speech in French! You needed a foreign language to get into university, so they let me sit French six times. I didn’t pass so I worked as a technician for a year. And then eventually I was let into Birmingham University.

What did it mean to you to win the Nobel prize?

The Nobel prize is the prize that everybody knows. I was fortunate that I got it on the 100th anniversary of the Nobel, so it was a great occasion. The fact is that I do talk more to the public and journalists now and it’s mainly because of the Nobel prize. Suddenly you become a public figure. You have to be careful you don’t say anything too stupid. In some countries such as India or China it’s a huge distinction, even in Germany and France. In the UK, we don’t tend to see it like that so much. In some ways, I think that’s a good thing.

- What Is Life? by Sir Paul Nurse is published on 3 September by David Fickling Books (£9.99). To order a copy go to guardianbookshop.com. Free UK p&p over £15

* See the original interview HERE

See also: Sir Paul Nurse: 'I looked at my birth certificate. That was not my mother's name'

“What is Life?” with Sir Paul Nurse: Watch the Video

On the 250th Birthday of William Wordsworth Let Nature be our Wisest Teacher

A Sure Path to build a Better World: How nature helps us feel good and do good

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 1973

‘The poet and the world’*

Wislawa Szymborska

(2 July 1923- 1 February 2012)

Nobel Lecture, December 7, 1996

‘Nobel prizewinner who viewed the world through poetry’

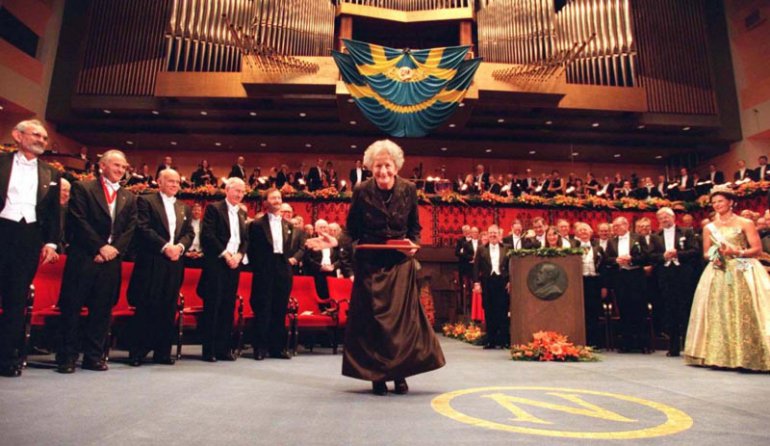

The Nobel Prize in Literature 1996 was awarded to Wislawa Szymborska "for poetry that with ironic precision allows the historical and biological context to come to light in fragments of human reality."- The Nobel Prize in Literature 1996

Wisława Szymborska acknowledges the applause from the audience, Stockholm, 1996, photo: REUTERS/FORUM

‘The poet and the world'

They say the first sentence in any speech is always the hardest. Well, that one’s behind me, anyway. But I have a feeling that the sentences to come – the third, the sixth, the tenth, and so on, up to the final line – will be just as hard, since I’m supposed to talk about poetry. I’ve said very little on the subject, next to nothing, in fact. And whenever I have said anything, I’ve always had the sneaking suspicion that I’m not very good at it. This is why my lecture will be rather short. All imperfection is easier to tolerate if served up in small doses.

Contemporary poets are skeptical and suspicious even, or perhaps especially, about themselves. They publicly confess to being poets only reluctantly, as if they were a little ashamed of it. But in our clamorous times it’s much easier to acknowledge your faults, at least if they’re attractively packaged, than to recognize your own merits, since these are hidden deeper and you never quite believe in them yourself … When filling in questionnaires or chatting with strangers, that is, when they can’t avoid revealing their profession, poets prefer to use the general term “writer” or replace “poet” with the name of whatever job they do in addition to writing. Bureaucrats and bus passengers respond with a touch of incredulity and alarm when they find out that they’re dealing with a poet. I suppose philosophers may meet with a similar reaction. Still, they’re in a better position, since as often as not they can embellish their calling with some kind of scholarly title. Professor of philosophy – now that sounds much more respectable.

But there are no professors of poetry. This would mean, after all, that poetry is an occupation requiring specialized study, regular examinations, theoretical articles with bibliographies and footnotes attached, and finally, ceremoniously conferred diplomas. And this would mean, in turn, that it’s not enough to cover pages with even the most exquisite poems in order to become a poet. The crucial element is some slip of paper bearing an official stamp. Let us recall that the pride of Russian poetry, the future Nobel Laureate Joseph Brodsky was once sentenced to internal exile precisely on such grounds. They called him “a parasite,” because he lacked official certification granting him the right to be a poet …

Several years ago, I had the honor and pleasure of meeting Brodsky in person. And I noticed that, of all the poets I’ve known, he was the only one who enjoyed calling himself a poet. He pronounced the word without inhibitions.

Just the opposite – he spoke it with defiant freedom. It seems to me that this must have been because he recalled the brutal humiliations he had experienced in his youth.

In more fortunate countries, where human dignity isn’t assaulted so readily, poets yearn, of course, to be published, read, and understood, but they do little, if anything, to set themselves above the common herd and the daily grind. And yet it wasn’t so long ago, in this century’s first decades, that poets strove to shock us with their extravagant dress and eccentric behavior. But all this was merely for the sake of public display. The moment always came when poets had to close the doors behind them, strip off their mantles, fripperies, and other poetic paraphernalia, and confront – silently, patiently awaiting their own selves – the still white sheet of paper. For this is finally what really counts.

It’s not accidental that film biographies of great scientists and artists are produced in droves. The more ambitious directors seek to reproduce convincingly the creative process that led to important scientific discoveries or the emergence of a masterpiece. And one can depict certain kinds of scientific labor with some success. Laboratories, sundry instruments, elaborate machinery brought to life: such scenes may hold the audience’s interest for a while. And those moments of uncertainty – will the experiment, conducted for the thousandth time with some tiny modification, finally yield the desired result? – can be quite dramatic. Films about painters can be spectacular, as they go about recreating every stage of a famous painting’s evolution, from the first penciled line to the final brush-stroke. Music swells in films about composers: the first bars of the melody that rings in the musician’s ears finally emerge as a mature work in symphonic form. Of course this is all quite naive and doesn’t explain the strange mental state popularly known as inspiration, but at least there’s something to look at and listen to.

But poets are the worst. Their work is hopelessly unphotogenic. Someone sits at a table or lies on a sofa while staring motionless at a wall or ceiling. Once in a while this person writes down seven lines only to cross out one of them fifteen minutes later, and then another hour passes, during which nothing happens … Who could stand to watch this kind of thing?

I’ve mentioned inspiration. Contemporary poets answer evasively when asked what it is, and if it actually exists. It’s not that they’ve never known the blessing of this inner impulse. It’s just not easy to explain something to someone else that you don’t understand yourself.

When I’m asked about this on occasion, I hedge the question too. But my answer is this: inspiration is not the exclusive privilege of poets or artists generally.

There is, has been, and will always be a certain group of people whom inspiration visits. It’s made up of all those who’ve consciously chosen their calling and do their job with love and imagination. It may include doctors, teachers, gardeners – and I could list a hundred more professions. Their work becomes one continuous adventure as long as they manage to keep discovering new challenges in it. Difficulties and setbacks never quell their curiosity. A swarm of new questions emerges from every problem they solve. Whatever inspiration is, it’s born from a continuous “I don’t know.”

There aren’t many such people. Most of the earth’s inhabitants work to get by. They work because they have to. They didn’t pick this or that kind of job out of passion; the circumstances of their lives did the choosing for them. Loveless work, boring work, work valued only because others haven’t got even that much, however loveless and boring – this is one of the harshest human miseries. And there’s no sign that coming centuries will produce any changes for the better as far as this goes.

And so, though I may deny poets their monopoly on inspiration, I still place them in a select group of Fortune’s darlings.

At this point, though, certain doubts may arise in my audience. All sorts of torturers, dictators, fanatics, and demagogues struggling for power by way of a few loudly shouted slogans also enjoy their jobs, and they too perform their duties with inventive fervor. Well, yes, but they “know.” They know, and whatever they know is enough for them once and for all. They don’t want to find out about anything else, since that might diminish their arguments’ force. And any knowledge that doesn’t lead to new questions quickly dies out: it fails to maintain the temperature required for sustaining life. In the most extreme cases, cases well known from ancient and modern history, it even poses a lethal threat to society.

This is why I value that little phrase “I don’t know” so highly. It’s small, but it flies on mighty wings. It expands our lives to include the spaces within us as well as those outer expanses in which our tiny Earth hangs suspended. If Isaac Newton had never said to himself “I don’t know,” the apples in his little orchard might have dropped to the ground like hailstones and at best he would have stooped to pick them up and gobble them with gusto. Had my compatriot Marie Sklodowska-Curie never said to herself “I don’t know”, she probably would have wound up teaching chemistry at some private high school for young ladies from good families, and would have ended her days performing this otherwise perfectly respectable job. But she kept on saying “I don’t know,” and these words led her, not just once but twice, to Stockholm, where restless, questing spirits are occasionally rewarded with the Nobel Prize.

Poets, if they’re genuine, must also keep repeating “I don’t know.” Each poem marks an effort to answer this statement, but as soon as the final period hits the page, the poet begins to hesitate, starts to realize that this particular answer was pure makeshift that’s absolutely inadequate to boot. So the poets keep on trying, and sooner or later the consecutive results of their self-dissatisfaction are clipped together with a giant paperclip by literary historians and called their “oeuvre” …

I sometimes dream of situations that can’t possibly come true. I audaciously imagine, for example, that I get a chance to chat with the Ecclesiastes, the author of that moving lament on the vanity of all human endeavors. I would bow very deeply before him, because he is, after all, one of the greatest poets, for me at least. That done, I would grab his hand. “‘There’s nothing new under the sun’: that’s what you wrote, Ecclesiastes. But you yourself were born new under the sun. And the poem you created is also new under the sun, since no one wrote it down before you. And all your readers are also new under the sun, since those who lived before you couldn’t read your poem. And that cypress that you’re sitting under hasn’t been growing since the dawn of time. It came into being by way of another cypress similar to yours, but not exactly the same. And Ecclesiastes, I’d also like to ask you what new thing under the sun you’re planning to work on now? A further supplement to the thoughts you’ve already expressed? Or maybe you’re tempted to contradict some of them now? In your earlier work you mentioned joy – so what if it’s fleeting? So maybe your new-under-the-sun poem will be about joy? Have you taken notes yet, do you have drafts? I doubt you’ll say, ‘I’ve written everything down, I’ve got nothing left to add.’ There’s no poet in the world who can say this, least of all a great poet like yourself.”

The world – whatever we might think when terrified by its vastness and our own impotence, or embittered by its indifference to individual suffering, of people, animals, and perhaps even plants, for why are we so sure that plants feel no pain; whatever we might think of its expanses pierced by the rays of stars surrounded by planets we’ve just begun to discover, planets already dead? still dead? we just don’t know; whatever we might think of this measureless theater to which we’ve got reserved tickets, but tickets whose lifespan is laughably short, bounded as it is by two arbitrary dates; whatever else we might think of this world – it is astonishing.

But “astonishing” is an epithet concealing a logical trap. We’re astonished, after all, by things that deviate from some well-known and universally acknowledged norm, from an obviousness we’ve grown accustomed to. Now the point is, there is no such obvious world. Our astonishment exists per se and isn’t based on comparison with something else.

Granted, in daily speech, where we don’t stop to consider every word, we all use phrases like “the ordinary world,” “ordinary life,” “the ordinary course of events” … But in the language of poetry, where every word is weighed, nothing is usual or normal. Not a single stone and not a single cloud above it. Not a single day and not a single night after it. And above all, not a single existence, not anyone’s existence in this world.

It looks like poets will always have their work cut out for them.

Translated from Polish by Stanislaw Baranczak and Clare Cavanagh

*This article was originally published in The Nobel Prize

Wisława Szymborska obituary, The Guardian, 2 February 2012

……

“I don’t know”

But, nonetheless, what I know is that:

Poetry is the key which unlocks the gates of wisdom

Poetry can help us lead a better life

Photo:open.edu

And

Here's why we shouldn't give up on poetry

Here’s why we need daily doses of poetry to nourish our hearts and nurture our souls

Reflecting on Life: My Childhood in Iran where the love of poetry was instilled in me

Poetry is the Education that Nourishes the Heart and Nurtures the Soul

Finding sanctuary in poetry during lockdown

Lockdown lawyers finding solace in poetry to deliver justice in times of COVID-19

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 3256

'Persian Poetry; a Precious Tradition, a Necessity for Life'

The poetry that can help you lead a better life

Here's why we shouldn't give up on poetry

Here’s why we need daily doses of poetry to nourish our hearts and nurture our souls

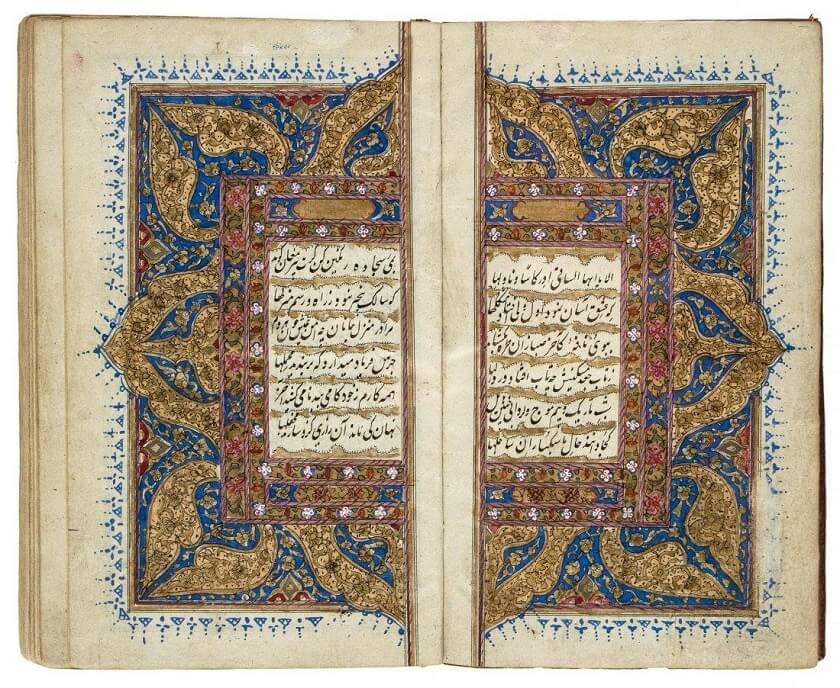

Manuscript of Hafez Diwan, decorated with Persian Tazhib drawings

Poetry is loved, appreciated and practiced by the Persians for many thousands of years. People of Iran live with poetry, breath and dream with poetry in all they do. Almost all of Iranian customs, traditions and way of life include poetry in one way or the other. Be it the presence of a book of Persian poetry, most commonly the Diwan of Hafez or Shahnameh of Ferdowsi or the Masnavi of Maulana Jalaluddin Rumi on the Haft-Sin tables that Iranians set for their New Year, or gathering together on Shab-e-Yalda and reading the Poems of Sa’adi and Hafez, or about wondering what to do, what path they should take in life, and more.

Reading Persian poetry aloud, apart from being an enjoyable pastime is believed by many Iranians as like being in an inspirational classroom, in which you can learn about life and human beings, the natural world and the sacred earth, or indeed, what it means to be human, as most of the Persian poetry is highly didactic. (Iran; the Land of Poetry)*

I remember so clearly and fondly all those decades ago, going to school in Tehran and our weekly classes in persian poetry, where under the supervision of our teacher we all recited poetry and enjoyed storytelling.

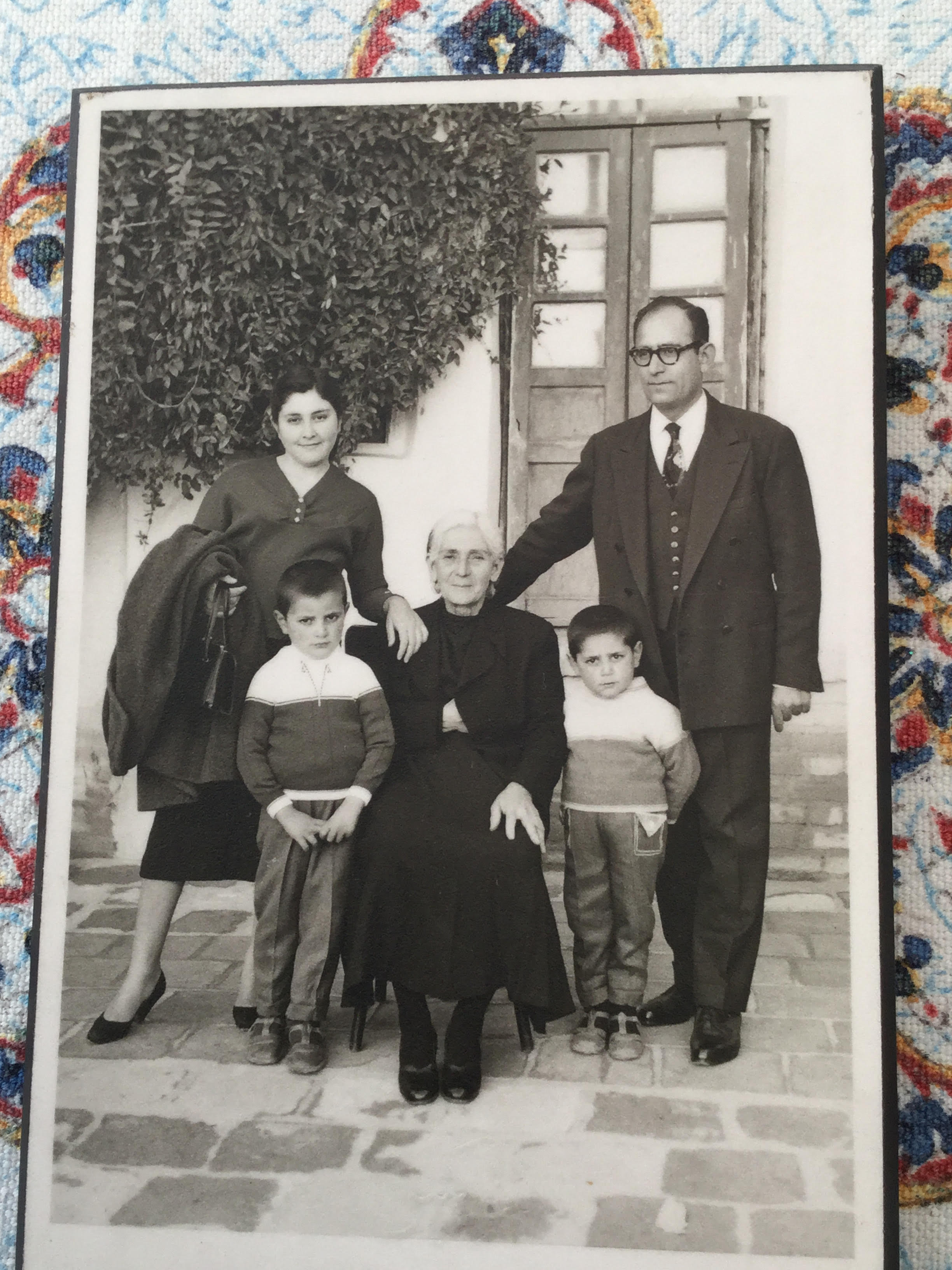

I was also blessed that the tradition of poetry reciting was very much honoured in our household too. My late father recited Rumi, Hafez, Sa’adi, Ferdowsi, Khayyam and many others to me and my brothers and sister as we grew up.

Indeed, life works in mysterious ways, when many years later in England, when I needed to rediscover myself and to heal myself spiritually, I finally chose to listen to my father and take heart in what he had recited to me all those decades ago in Tehran.

My mum and dad, grandma Mofid, myself on the left and my younger brother Kambiz. Tehran, Circa 1957

How Persian Mystic Poets Have Changed My Life

I learnt my love of mysticism and appreciation of mystic poetry from my late father, a businessman by trade and a connoisseur of Sufi poetry by tradition. For my father, nothing was more sacred than poetry — specifically the Persian mystical poetry. To him the Persian poets were the true sages, the gems of humanity, the philosophers of love, beauty and wisdom.

I remember he used to tell me all the time that, Kamran ‘These mystical poets can help you lead a better life, I am sure when you get older you will discover that for yourself.’ Reflecting back now, I can only say how right he was.

A few years back, when I came to realise that there was something amiss with much of the things that I had learnt about Western modern economics, its lack of moral and spiritual values, it was Rumi and other Persian sages such as Sa'adi and Hafez who came to my assistance in founding Globalisation for the Common Good Initiative, to bridge the divide between East and West, and to enable me to connect my intellect and my humanity. They enabled me to discover life’s bigger picture, beyond profit maximisation, cost minimisation, the so-called market forces, privatisation, deregulation, and free trade and more.

All said and done, they have allowed me to rediscover myself, my spiritual roots, enabling me to heal myself spiritually. More importantly, they have empowered me to discover, learn and appreciate other mystic traditions and sages. For this discovery of beauty, wisdom and inner-peace I cannot be grateful enough.

And this is why Poetry helped me to remain hopeful and positive during the COVID-19 Lockdown

Below you can see a sample of the articles and Blogs that I have posted on the GCGI.INFO to celebrate and honour the wonders and beauty of Persian mysticism, poetry, literature, history, arts, culture and civilisation.

Photo: The BBC

Wisdom of the East: Love and Wisdom of Sufism, Rumi and Hafez

Rumi and Saint Francis of Assisi: Sages for Today

In search of beauty, wisdom and love? Then, come, come, whoever you are come

Shahnameh: The Epic of the Persian Kings

COVID-19, isolation, reflection, fear, hope, beauty and wisdom: “Feathers of Fire”

Zoroastrianism the ancient religion of Persia that has shaped the world

On the 1st Day of the New Year...A Poetic Pilgrimage to Wisdom

Happy Norouz: It's nature's time for renewal, rejuvenation and happiness

How to defeat hatred and fear: Don't Despair Walk On

The Art of Persia: The Everlasting Magnificent Story of Beauty, Wisdom and Love

Modern Iran: The Most Misunderstood Country

Happy Shab-e Yalda: When Light Shines and Where Goodness, Beauty and Wisdom Prevails

'Lioness of Iran’: Simin Behbahani- RIP

Modern Iran: The Most Misunderstood Country

The Cyrus Cylinder: Ancient Persia’s Gift to the World

Revisiting the Persian cosmopolis: The World Order and the Dialogue of Civilisations

Cradle of god: Spirituality in the Land of the Noble

* Iran; the Land of Poetry

- Poetry is the Education that Nourishes the Heart and Nurtures the Soul

- The Emperors with no clothes: The Madness of King Donald- A Modern Day King John

- GCGI Celebrating Activism and Hope with British VOGUE

- Remembering Japan’s Ambassador’s Visit to Coventry, 25 Years On

- A Lesson for the COVID-19-Riddled World: Green Legacy of Hiroshima- Spreading Seeds of Hope and Peace All Over the World